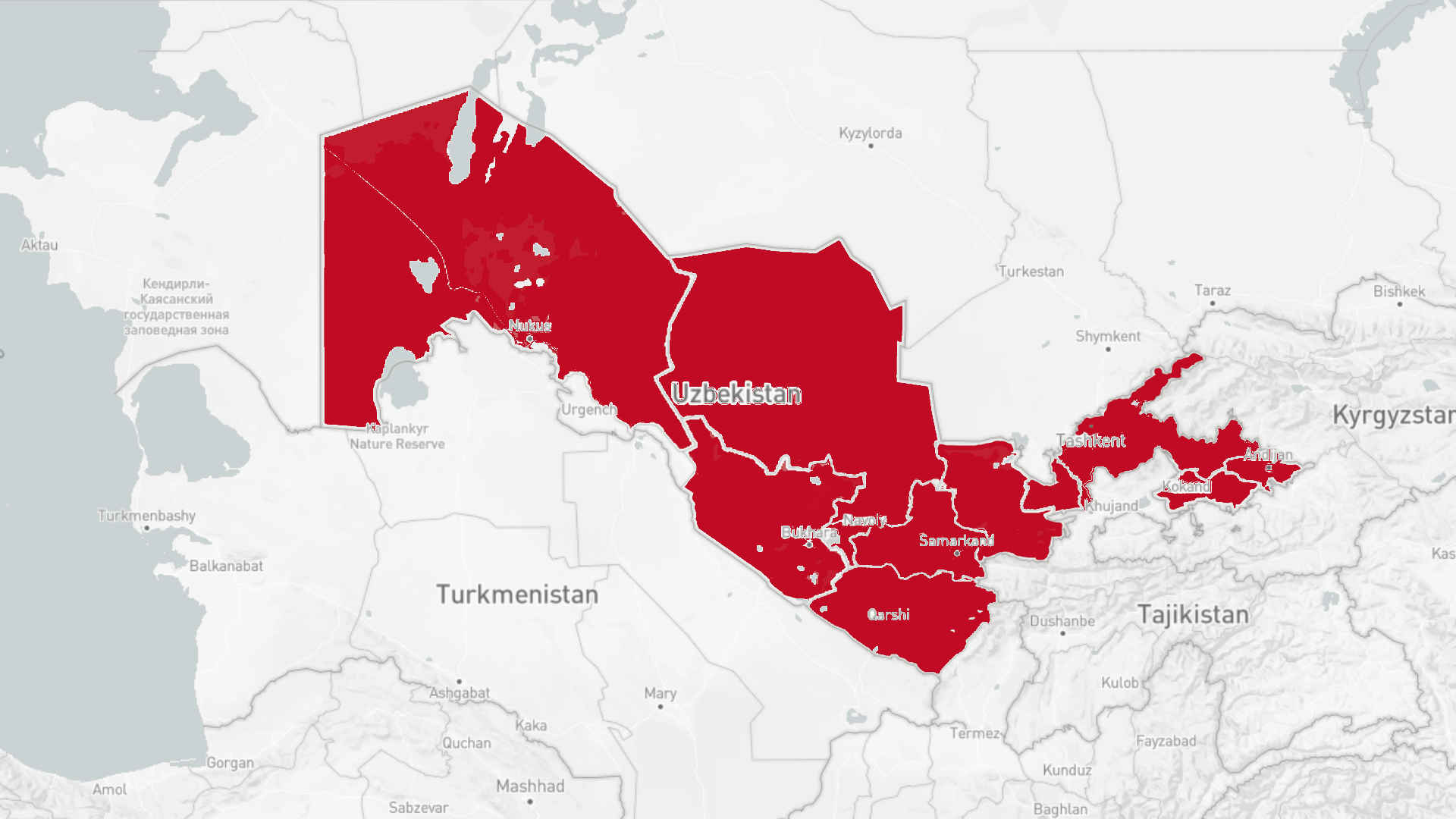

Social Media in Uzbekistan

Seeds of Reformation

written by

Lukas Fortkord

The Importance of Social Media in Central Asia is growing. Journalists and bloggers also use Facebook and Co. for their work and criticism of the government - thereby put themselves in danger.

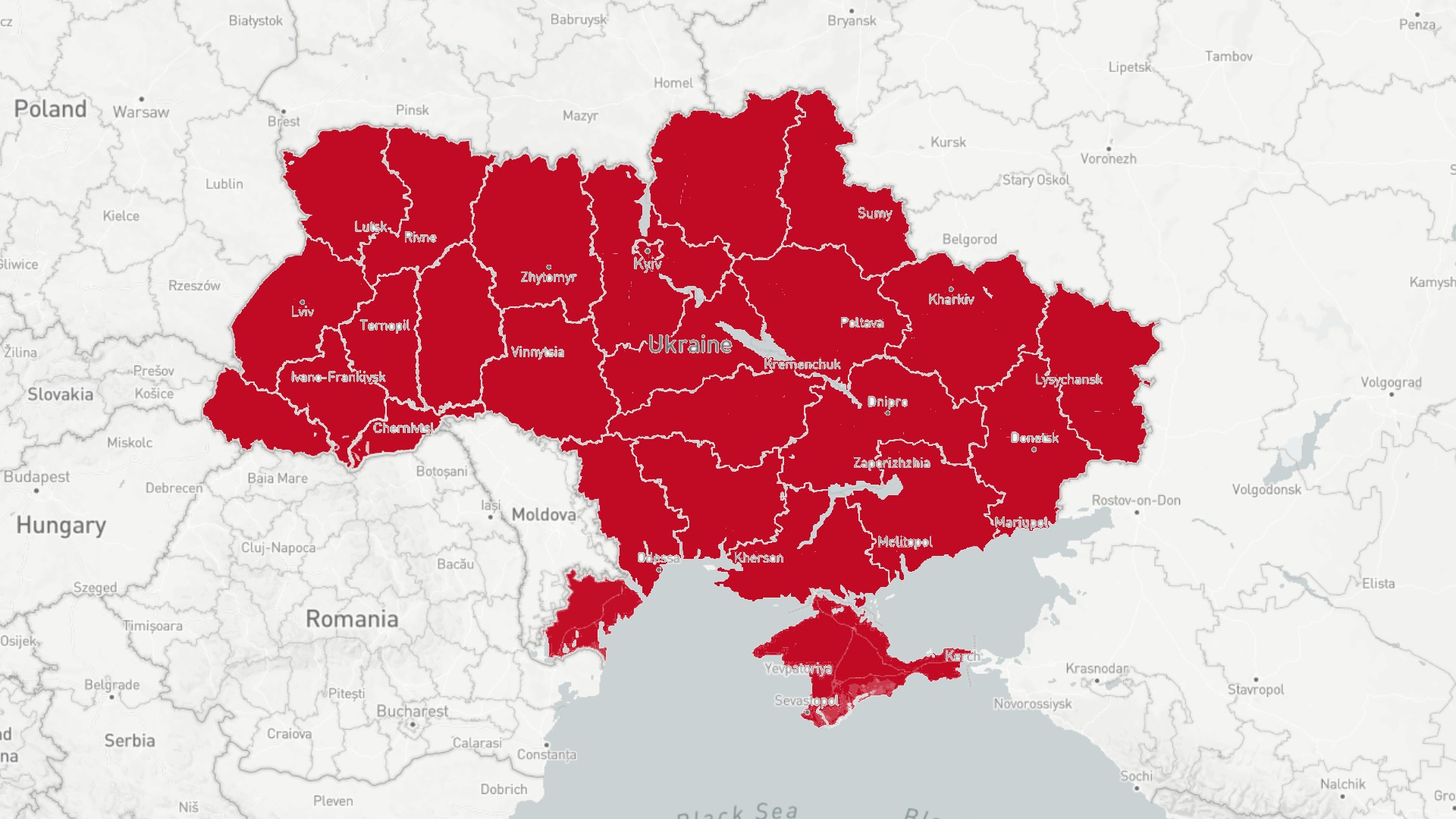

The use of the Internet, and primarily social media in Uzbekistan, has exploded. In the year 2000, there were only an estimated 7000 users, compared to an estimated 12.7 million users in 2015. Many of the over 30 million Uzbeks have made the Internet their preferred tool for expressing opinions that have long been banned from traditional media – some of which still are. Social media outlets are the only non-governmental platforms that reach millions of Uzbeks every day. Since Uzbeks began to use the Internet two decades ago, government agencies have recognized online news and social media as serious threats. The Islam-Karimov regime created no less than 38 Uzbek social networks between 2000 and 2016, with the aim of luring citizens and potential critics to platforms that are easier to monitor.

Facebook and its clones

After the death of the authoritarian ruler Karimov, Shavkat Mirziyoyev took over government affairs. He has since been trying to make “the dark era” forgotten, with limited success. Mirziyoyev has taken a mixed approach to media issues since taking power in December 2016, by combining superficial liberalization with continued harassment and censorship of critical news sources. At his command, nine prominent journalists were released from prison, and several prominent foreign news sites such as “Voice of America” and “Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty” were also unlocked. However, other websites remained blocked or were blocked again, and in early 2018, Bobomurod Abdullayev, a regular member of the “Ferghana news agency”, was arrested and allegedly tortured by Uzbek security forces for conspiracy to overthrow the regime. President Mirziyoev has announced an agenda aimed at decreasing Uzbekistan's international isolation, establishing "a dialogue" between the authorities and ordinary people, and mending tense ties with neighboring Central Asian countries. In October 2017, Human Rights Watch (HRW) said, that Uzbek authorities had taken "some positive steps" during Mirziyoev’s first year, and that freedom of the press has slightly increased.

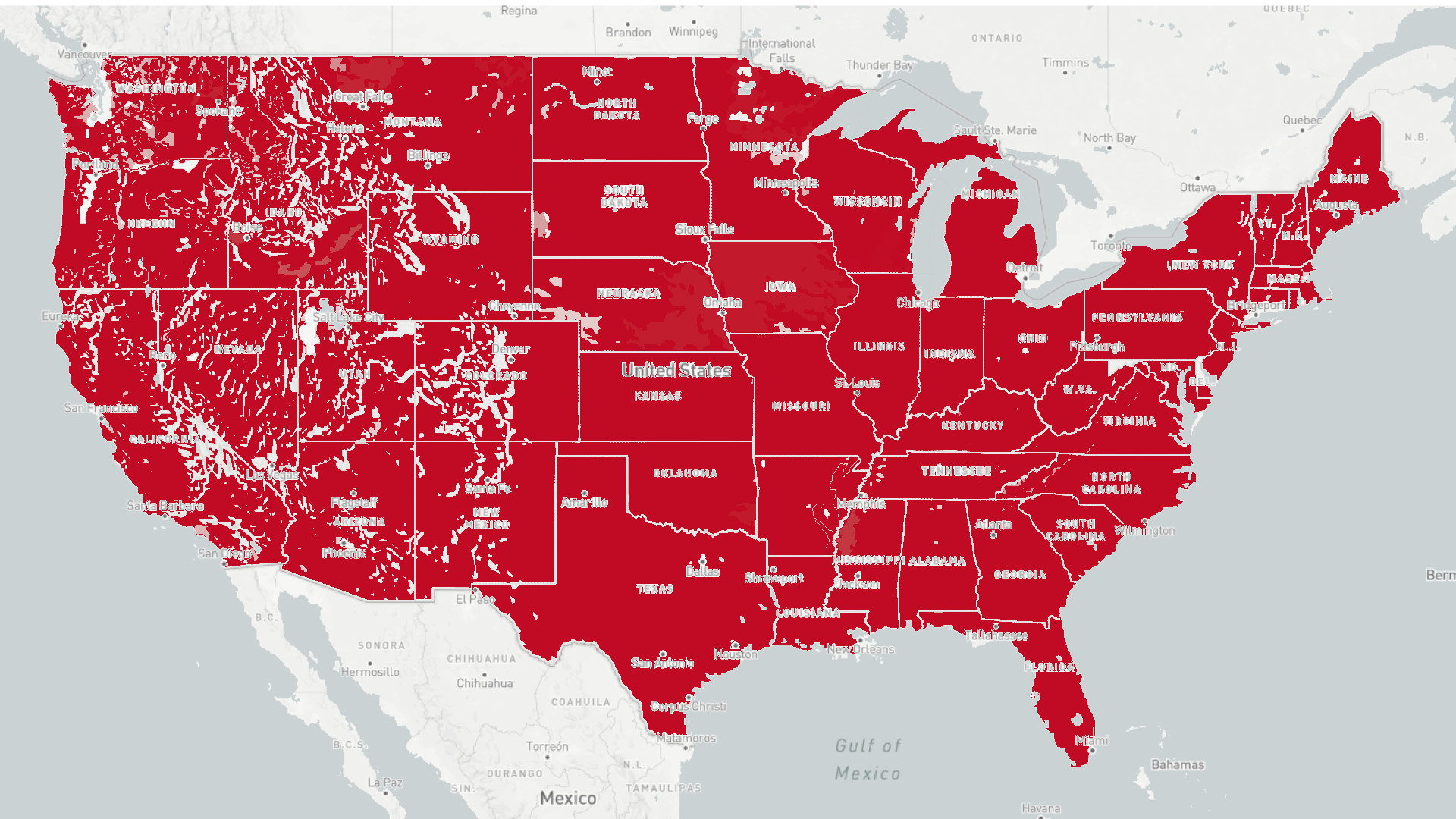

But the advances in media freedom remain limited. Censorship is still very present. In addition, some government platforms are still active. The most popular, Muloqot.uz, now only has a modest 170,000 users, Davra.uz, a Facebook clone that started in 2016, has no more than a few thousand users. In contrast, Facebook is a front runner in Uzbekistan, closely followed by the Russian social networks Odnoklassniki and VKontakte. Twitter has also recently become increasingly popular. This is shown by a study by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting: Of 86 Uzbek journalists, almost 90 percent use Facebook, and around a third use Instagram and Twitter. The government's platforms play a very small and insignificant role.

Break the monopoly

For many critics, social networks without government participation are the only way to publish dissenting opinions. This is because almost all regional media in Uzbekistan is financed from municipal budgets. Their actual premises are often located in government buildings, and the government bills them for rent and utilities. The consequences are predictable: instead of trying to track down, research and analyze problems, reporters are more of a channel for disseminating information on behalf of the authorities.

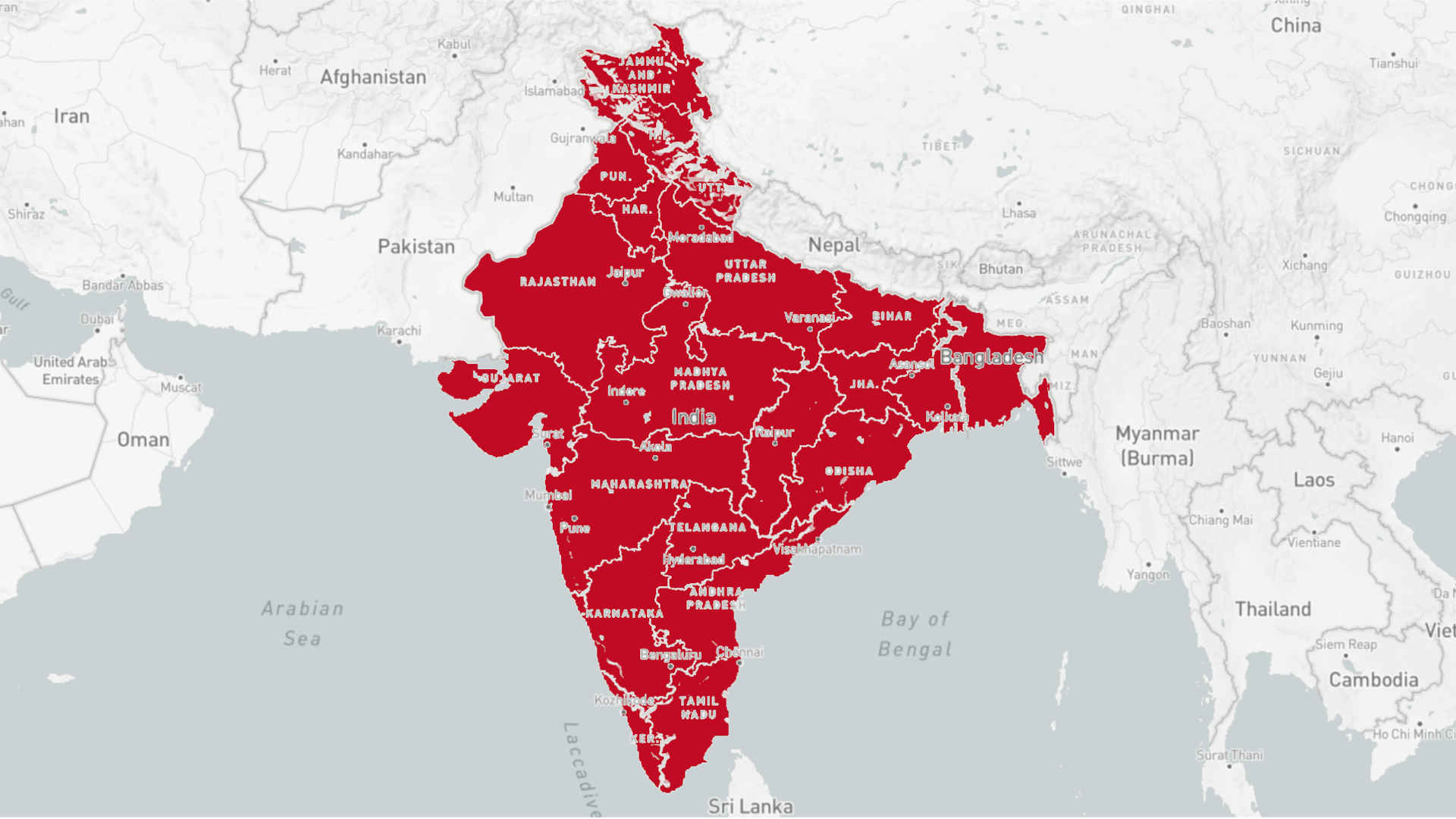

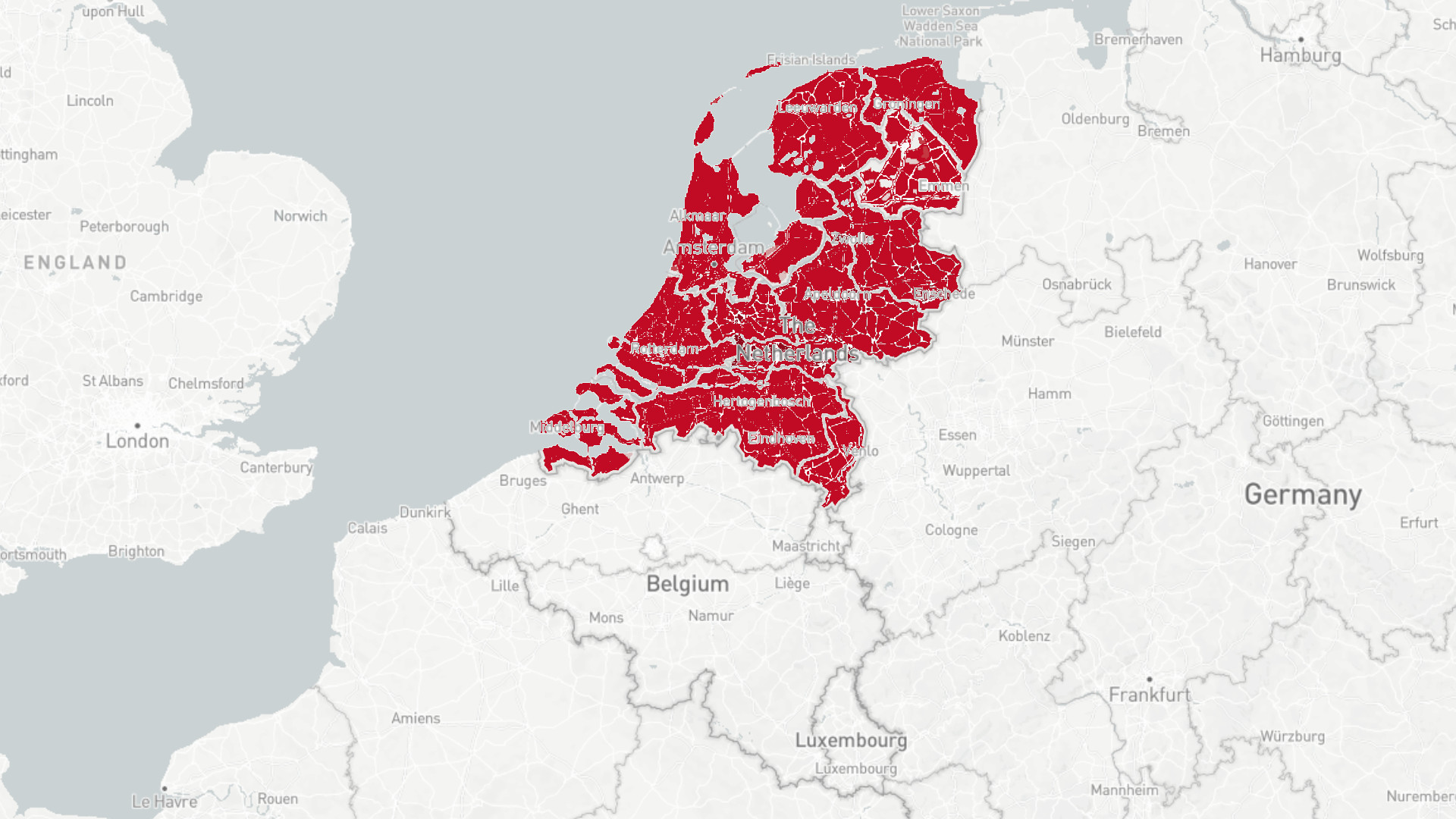

A few years ago, it was still unimaginable in Uzbekistan that internet bloggers and journalists could publicly oppose the government. Today, that is different. Since Karimov's death in 2016, more and more bloggers and journalists have begun expressing criticism of public officials under his successor Shavkat Mirziyoev. Some people, armed with smartphones and social media accounts, want to hold the government of Uzbekistan accountable. In doing so, they put themselves in danger, because they break through the state's monopoly on information and attack it via the platforms. It is no surprise that the relationship between the state and bloggers is tense. Nafosat Olloshukurova felt this personally. The mother of two children from Urgench in Western Uzbekistan, blogs mainly on Facebook under the name Shabnam Olloshukurova. In her posts, the journalist and blogger has repeatedly criticized the Uzbek government and has accused the authorities of corruption. In September, she reported on Facebook Live from journalist Mahmud Rajabov. Rajabov had made his way to the capital Tashkent on foot in order to contact the Interior Minister personally, because he was accused of being in possession of banned books. Olloshukurova filmed how police turned against peaceful demonstrators, protesting alongside Mahmud Rajabov against the government. In the same month, Olloshukurova herself was arrested and taken to a detention center for 10 days and charged with "hooliganism" and "attending unauthorized gatherings”. As a result, a court in the City of Urgench ordered a forced committal into a psychiatric clinic. The prosecutor previously said that Olloshukurova behaved "abnormally" and may have a "mental disorder". Although she was finally released, Olloshukurova decided to leave the country and seek asylum in Ukraine in January, fearing that she could again become a victim of the system.

Empty Words?

Is there hope for bloggers and Co.? Saida Mirziyoyeva, the daughter of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and, until a few months ago, deputy head of the state agency for information and mass communication, spoke at the first World Influencer Congress in Tashkent last year. Saida Mirziyoyev spoke of plans to legally equate Uzbek journalists and bloggers to provide them with legal protection. So far, nothing has happened. Shavkat Mirziyoyev himself seems to have recognized the importance of social media and bloggers - also for the image of Uzbekistan. The country is ranked 156th out of 180 in the press freedom index by “Reporters Without Borders”. In August 2019, while visiting Samarkand, Mirziyoyev said that he wanted to support bloggers. The measures for this seem to initially apply only to foreign influencers and bloggers. Influencer events that invite international social media influencers to Uzbekistan, are the latest in a series of unprecedented government moves to open up to the outside world and increase economic growth for its 30 million citizens -in hopes to polish up their image. This will most likely not improve freedom of the press, nor the security of critics. Uzbek bloggers still have a long struggle ahead of them.