Rewarding genocidal policies?

The EU-Mercosur free trade agreement was supposed to become a beacon of free trade. But as the Bolsonaro-backed slash-and-burn agriculture threatens indigenous peoples and the global climate, European leaders put their foot on the brake. What are the prospects of the deal?

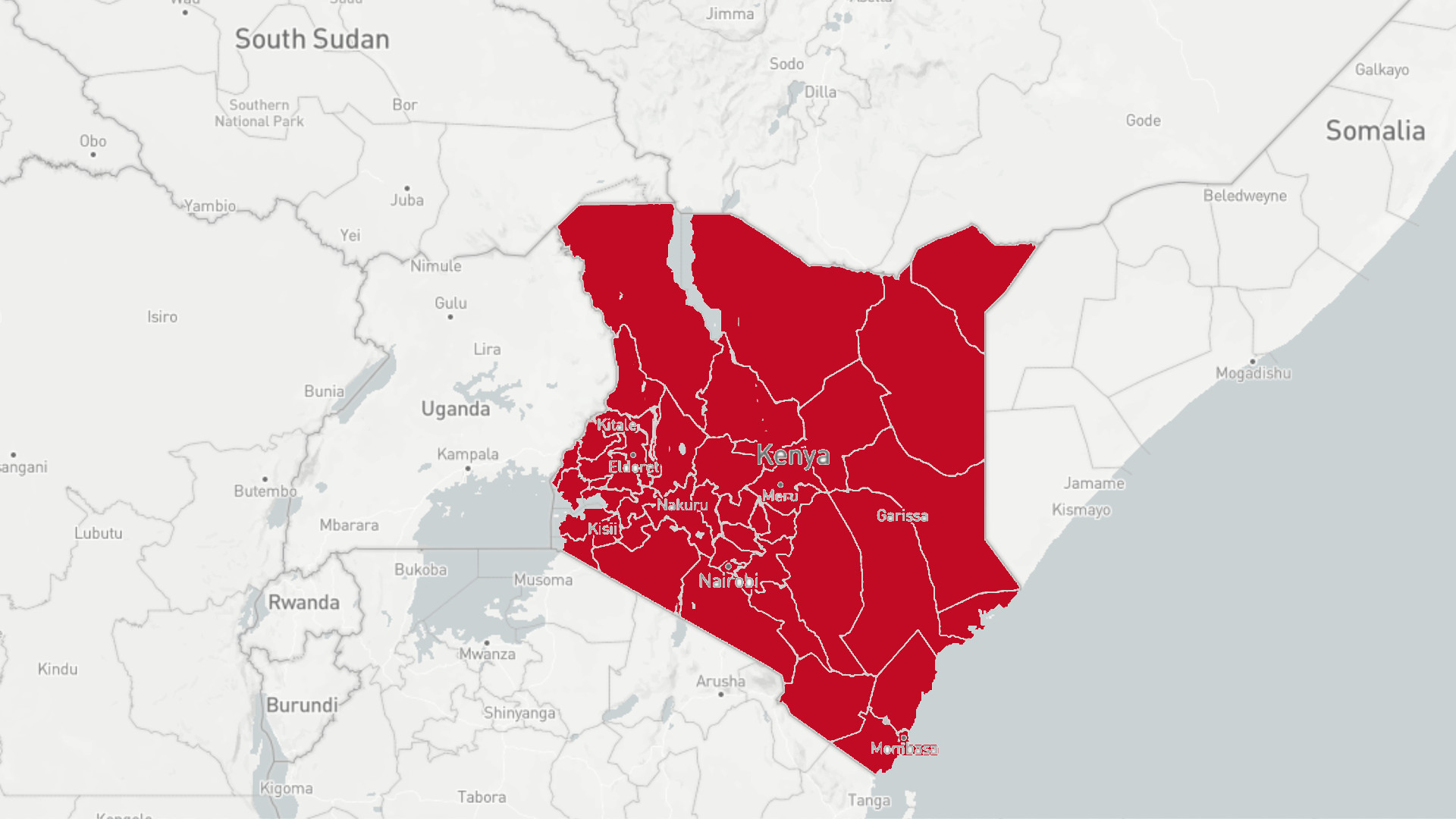

The acreage in Brazil that is used for soy nearly equals the size of Germany, and as far as the Bolsonaro government is concerned, it will soon be more. From the beginning of his presidential campaign, the right-wing leader wooed the Brazilian agribusiness, promising to promote the deforestation of the Amazon, where indigenous reservoirs shall give way for enormous soy fields. However, a major deal that should have boosted this commercialization now seems to be all but entrenched: the EU-Mercosur free trade agreement. While the Brazilian agribusiness and the German industry were just waiting to finally ship their goods around the globe, others fear the deal’s consequences. Sustainable farmers in Germany worry that they cannot compete with the genetically modified and pesticide-sprayed crops from abroad. And in Brazil, indigenous peoples’ stakeholders warn that the deal will further promote the government’s “genocidal policy” against them. Ultimately, even Angela Merkel, a former advocate of the deal, now expressed doubts over it. Are its opponents gaining momentum?

For Dinaman Tuxá, the matter is clear: The European Union can now decide either to assist the Brazilian agribusiness in their slash-and-burn strategy, or to side with indigenous people. “They need to be aware that the agreement will finance deforestation and violence against indigenous peoples”, says Tuxá, a lawyer and executive coordinator of the NGO “Articulation of Indigenous Peoples” (Apib). The Bolsonaro government left no doubt about its guidelines in this regard, Tuxá adds, denouncing a “complete dismantling of the state structure with regard to the rights of indigenous peoples and environmental rights”.

As a matter of fact, the clash with indigenous peoples has become one of the striking patterns of Bolsonaro’s presidency. As one of his first steps after taking office in January 2019, he dismantled the indigenous affairs agency FUNAI, giving away its competence to demarcate indigenous reservoirs to the agribusiness-friendly Agriculture Ministry. Since then, indigenous stakeholders bemoan an increase of attacks by illegal miners and loggers – in part because of a lack of inspection operations by the police. According to Human Rights Watch, fines for illegal logging in the Amazon haven been “effectively suspended” since October 2019.

And the increasing lawlessness is fortified by farmers’ prospects for profit. For years, soy acreage in Brazil has expanded and carved a path in the rainforest, where many indigenous peoples live. A trend that is likely to be fueled by a rising demand through the EU-Mercosur deal. “This expansion will open a new agribusiness front, especially in the Amazon”, warns Tuxá, holding the EU “co-responsible” for possible crimes in the future. “There will be funding for genocide and ethnocide in Brazil if this agreement is signed on the terms in which it is found.”

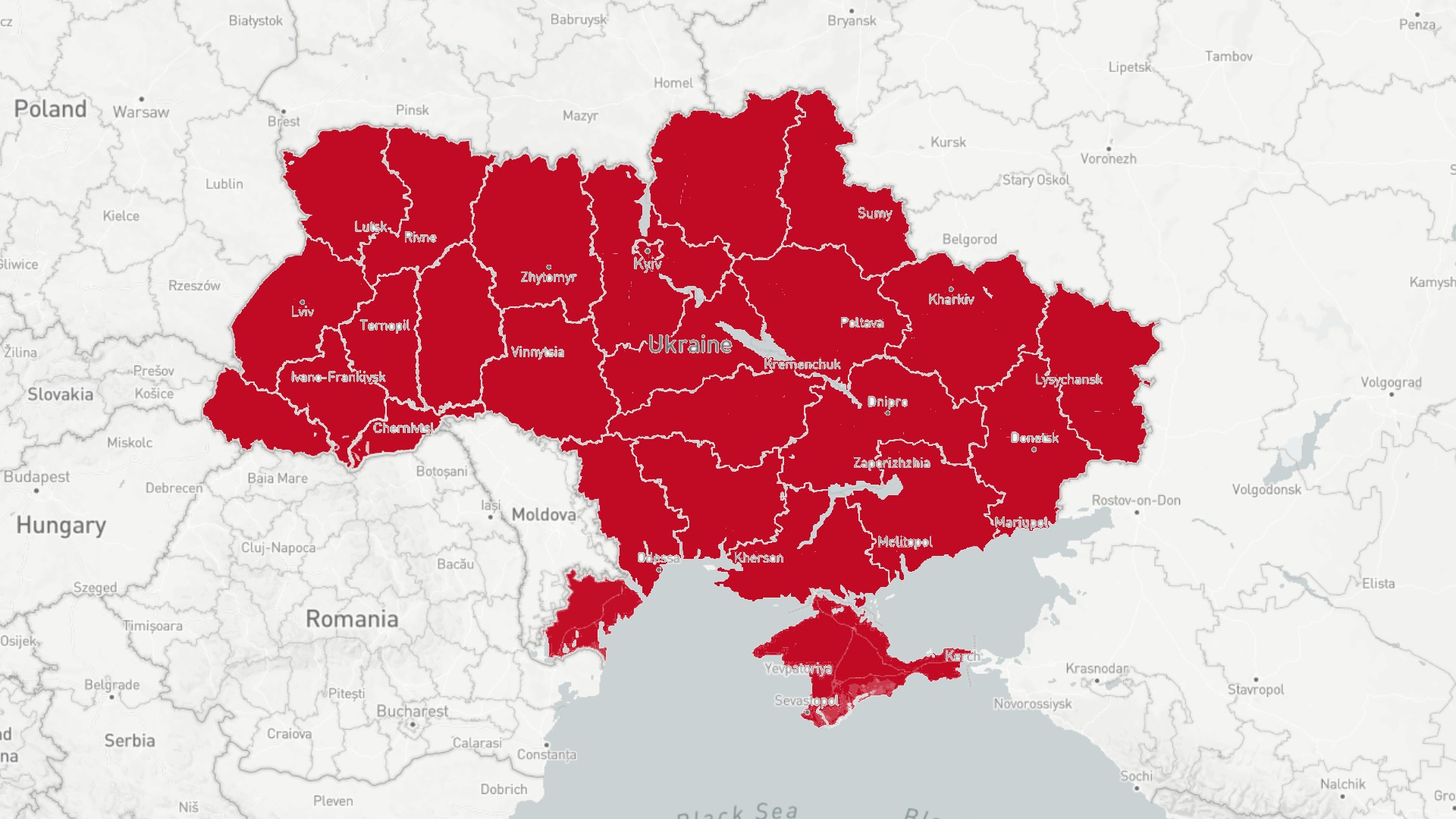

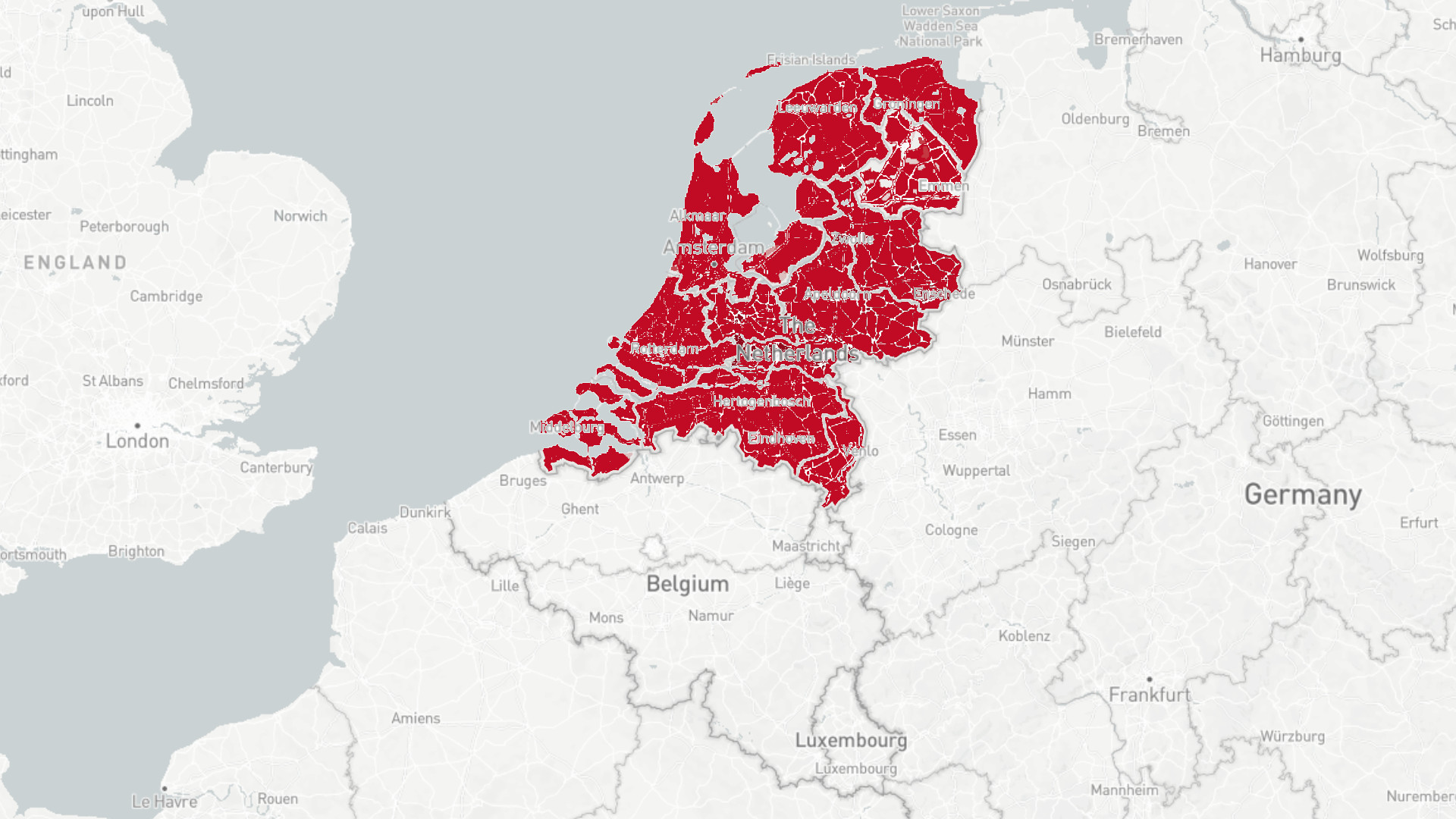

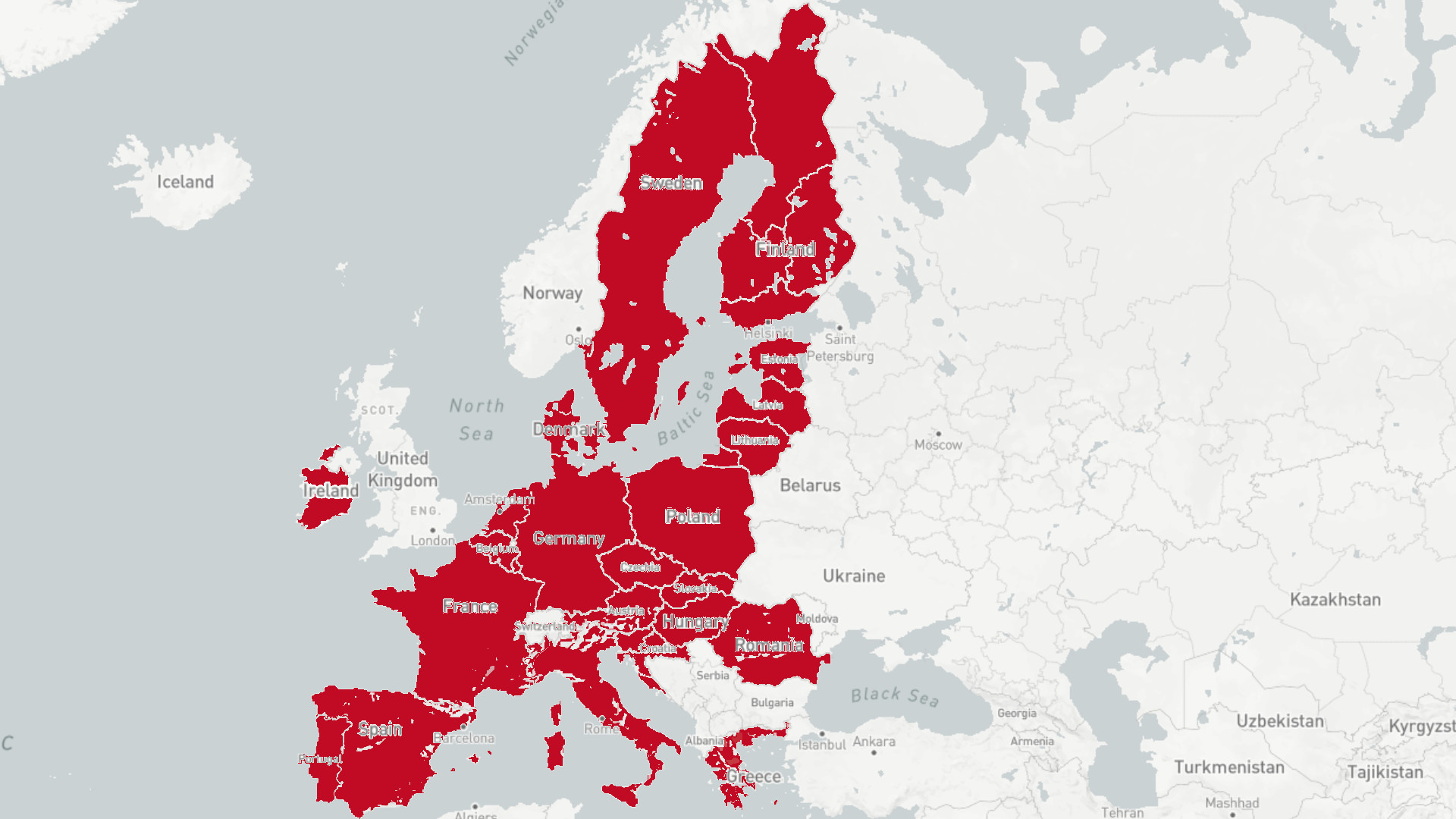

Originally, the free trade agreement between the European Union and the Mercosur states Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay was meant to become a beacon of free trade. In a time of growing protectionism, it aimed to create a trade area of unprecedented scope. Comprising 780 million people and some 25 per cent of the global GDP, it would have provided a fertile playground for strong export countries like Germany and Brazil. The relief was accordingly strong when leaders from the EU and Mercosur announced their negotiation success at last year’s G20 Summit in Osaka. “This is the end of a 20-years-long negotiating history”, said Angela Merkel. However, the deal is yet to be ratified by every single member country. And on the European side of the Atlantic, too, stakeholders and politicians expressed their doubts about its meaningfulness. Austria, the Netherlands and Wallonia already declared to vote against the deal, for which unanimity is required. Ireland, Luxembourg, France and a multitude of NGOs expressed a reluctant attitude as well. In part, they bring up arguments in connection with global warming, arguing that under Bolsonaro the deforestation of the Amazon, the world’s green lung, has sped up. On the other hand, they fear that food standards in the EU will be undermined, as the products from abroad are often genetically modified or treated with pesticides that are forbidden in Europe. Finally, beef farmers in the EU have protested against the agreement, fearing cheap Brazilian beef will flood the European market that already produces more meat than it can consume itself.

“It is obvious, that there is a double standard in place”, says Wilhelm Eckei, a German cattle farmer, who has been engaged in sustainable agriculture for thirty years. “On the one hand, we are supposed to produce more environmentally friendly, which is in part subsidized. On the other hand, we then import the exact opposite of that”, Eckei says in an interview with the German TV-magazine “Monitor”. “It just doesn’t make any sense.”

In Germany, pressure to vote against the agreement increased lately, as Angela Merkel’s government took over presidency of the European Council; a position from which Merkel originally wanted to promote the trade deal, but now faces headwinds. In June, more than 60 NGOs protested in Berlin against the agreement. And in late August, Merkel met with Greta Thunberg and other Fridays for Future activists, eventually expressing “considerable doubts” about the ratification of the agreement.

In talks he had with members of the European Union Dinaman Tuxá noted, too, that many of them were “very receptive and were very fearful” in regard to the agreement. Even if the final word is yet to be spoken, he acknowledges: “With no doubt, the international community is much more sensitive to the rights of indigenous peoples than the Brazilian government.”

But even beyond the free trade agreement, Tuxá calls on European leaders to seek traceability of their products from Brazil. And, subsequently, to penalize “companies that commit or foment socio-environmental crimes, such as slave labor, that invade indigenous lands, that foster socio-environmental conflicts.” Legal mechanisms like that are necessary, he says. Not just to save indigenous lives, but to keep the Amazon, the world’s green lung, from vanishing.