Pen, paper, and Twitter

The role of Twitter in modern journalism.

written by

Léonardo Kahn

What would a journalist take to a deserted island? A Swiss army knife? A can of beans? Perhaps a box of Gauloise, which he pushes meticulously one after another into his mouth while the typewriter clicks faster, and the stack of paper that will later become his story grows? Egon Erwin Kisch would probably have preferred the latter, but journalism is changing - through education on the effects of tobacco consumption, and through digitalisation. Today, the Raging Reporter is less likely to have a cigarette between his lips than to have a mobile phone in his pocket. The journalists' new favourite tool is Twitter: A social platform with side effects.

Twitter has been online since 2006, and seven years later it became one of the ten most frequently visited websites worldwide. One may wonder why, since the app is not particularly attractive- modest at best. At the top of the screen, you see the blue silhouette of a bird. On the left, the grin of your own profile picture and on the right side, a button to play around with the settings. And below: an infinite amount of text. Every user has 240 characters per tweet. While scrolling, you might meet an emoji, and if you’re lucky. sometimes even a picture. Mostly, you’ll only find numbers and letters. Facebook lures users with its versatility, and Instagram, with being a pure visual platform, meaning that it is a photo album and social media at the same time. Twitter, on the other hand, has little more to offer than words. And that seems to be the exact reason for its success.

Anyone who sets up a Twitter account today, is not doing so to keep in touch with old schoolmates, or to upload holiday photos. It is because of the conviction that their opinion matters enough to shout it out into the vastness of the net, or because they are interested in other people’s opinions. As a result, Twitter users are much more political than in other social media, which makes it an excellent breeding ground for stars, politicians, and last but not least, journalists.

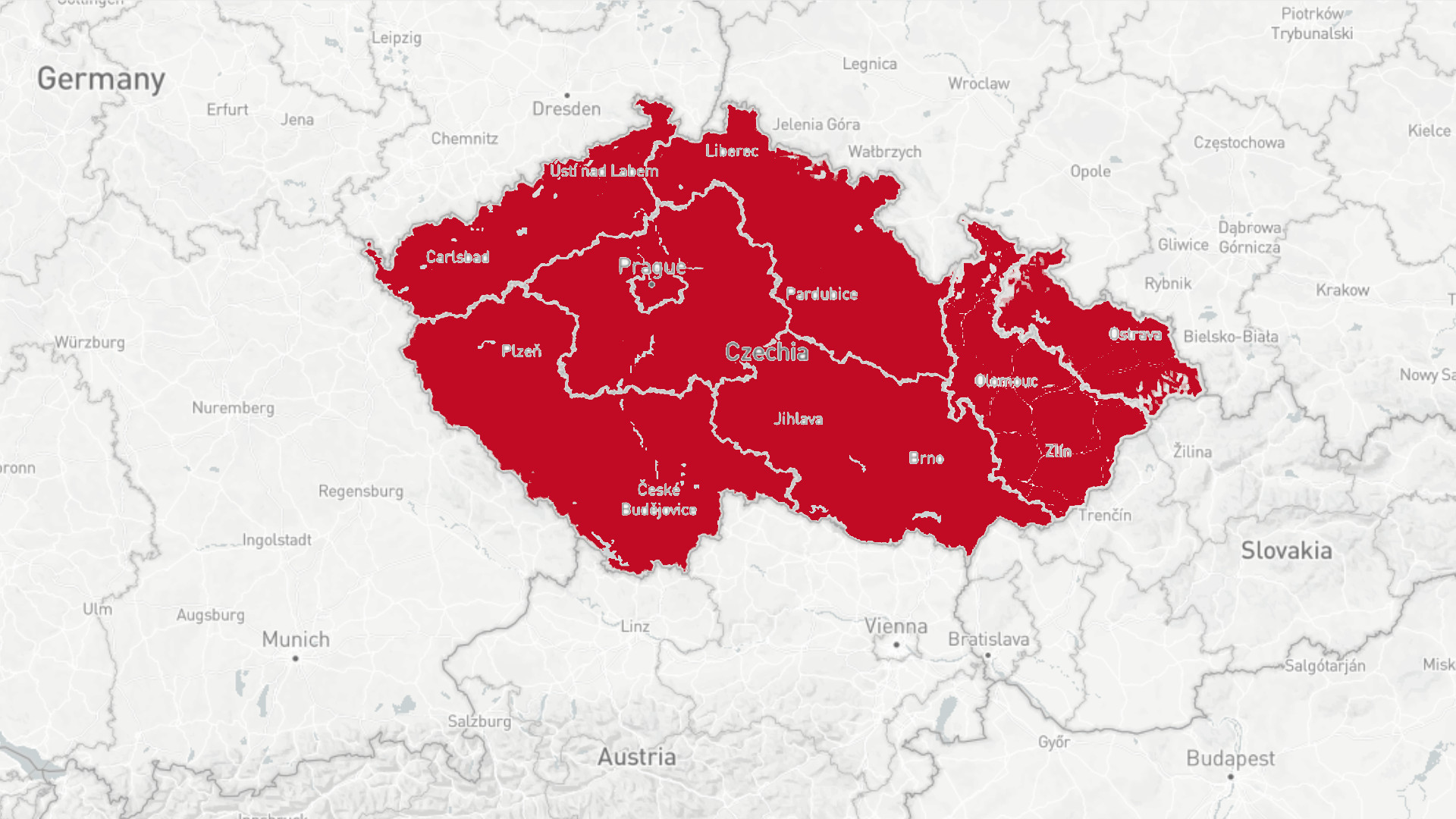

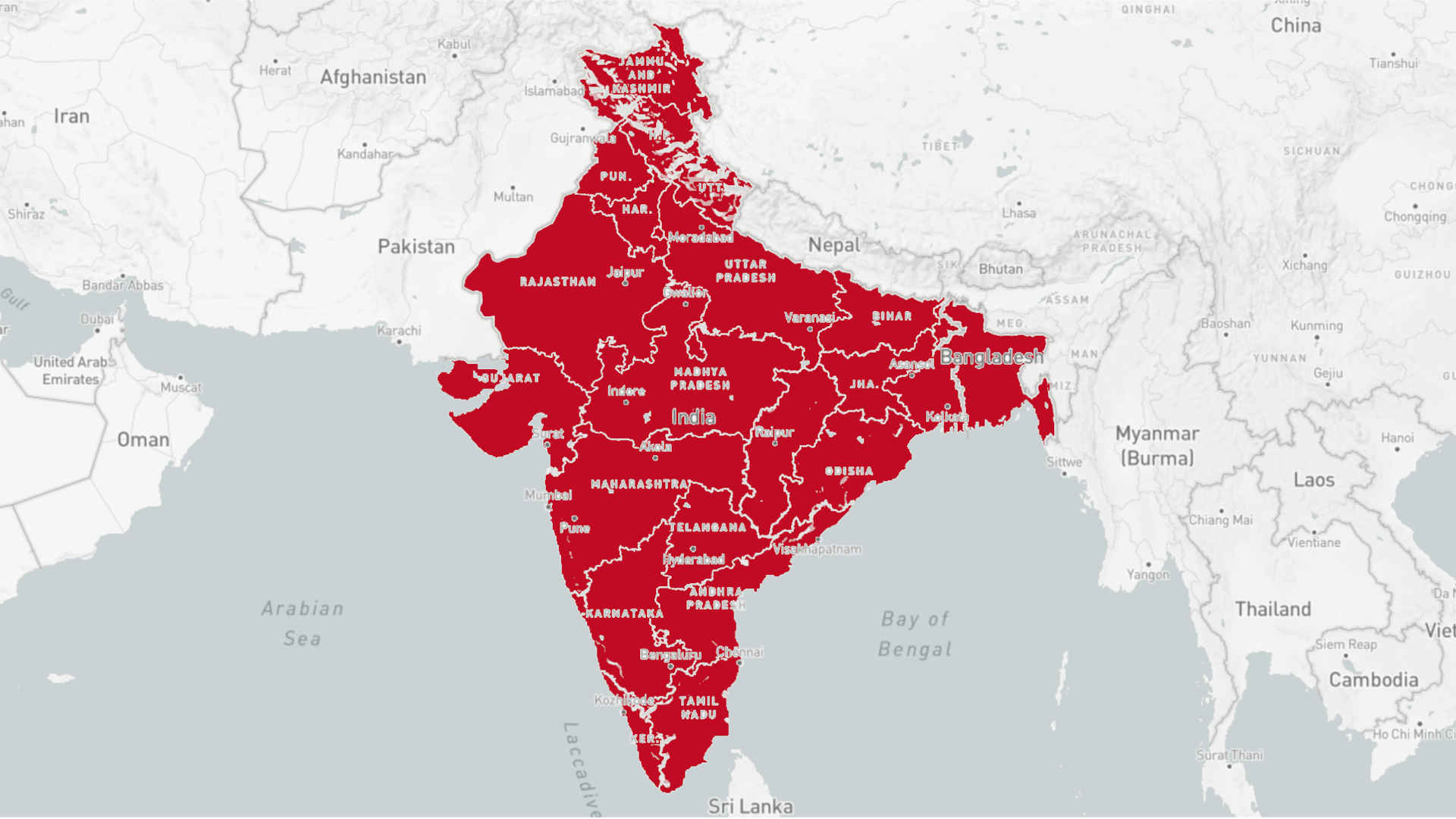

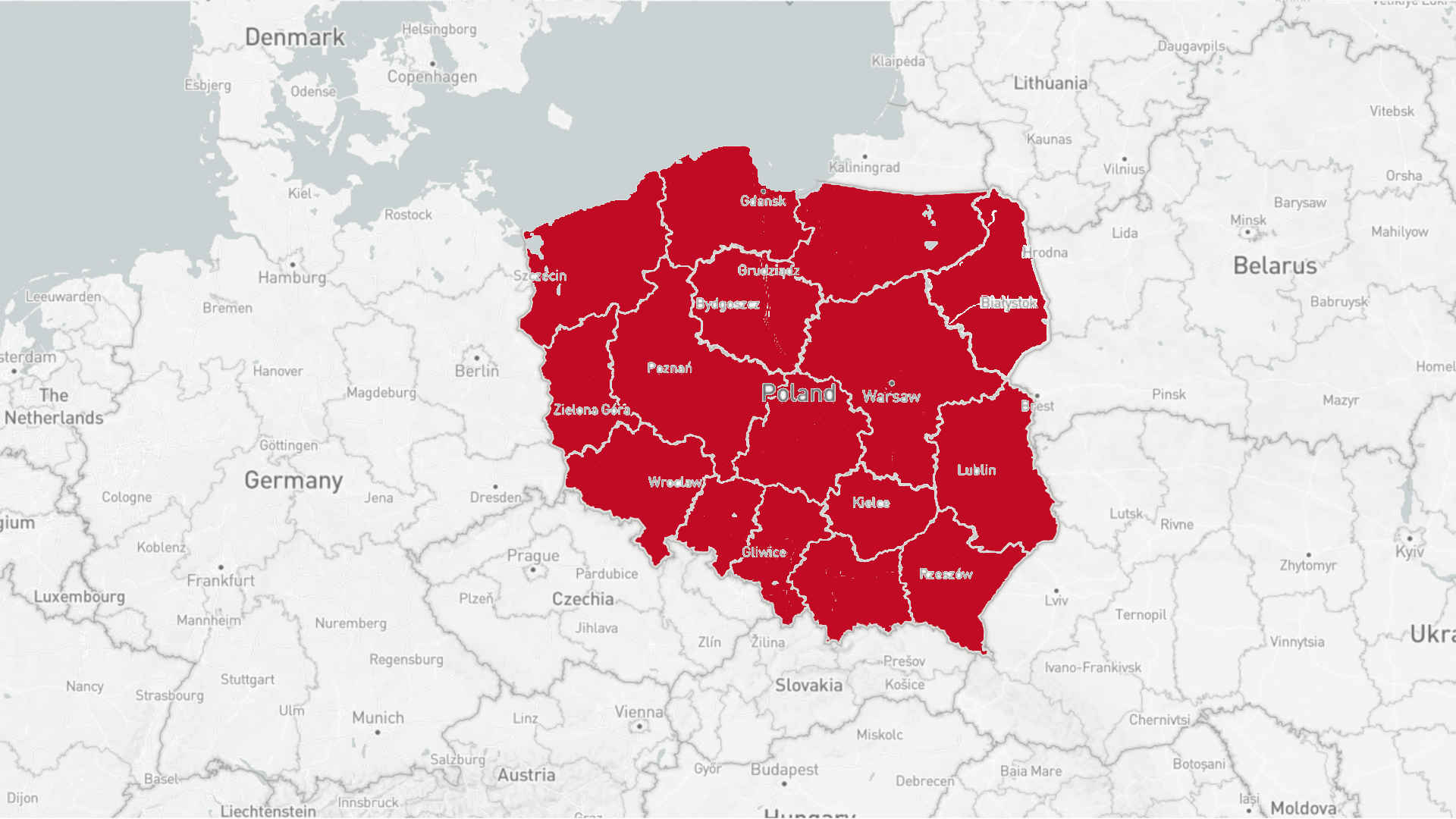

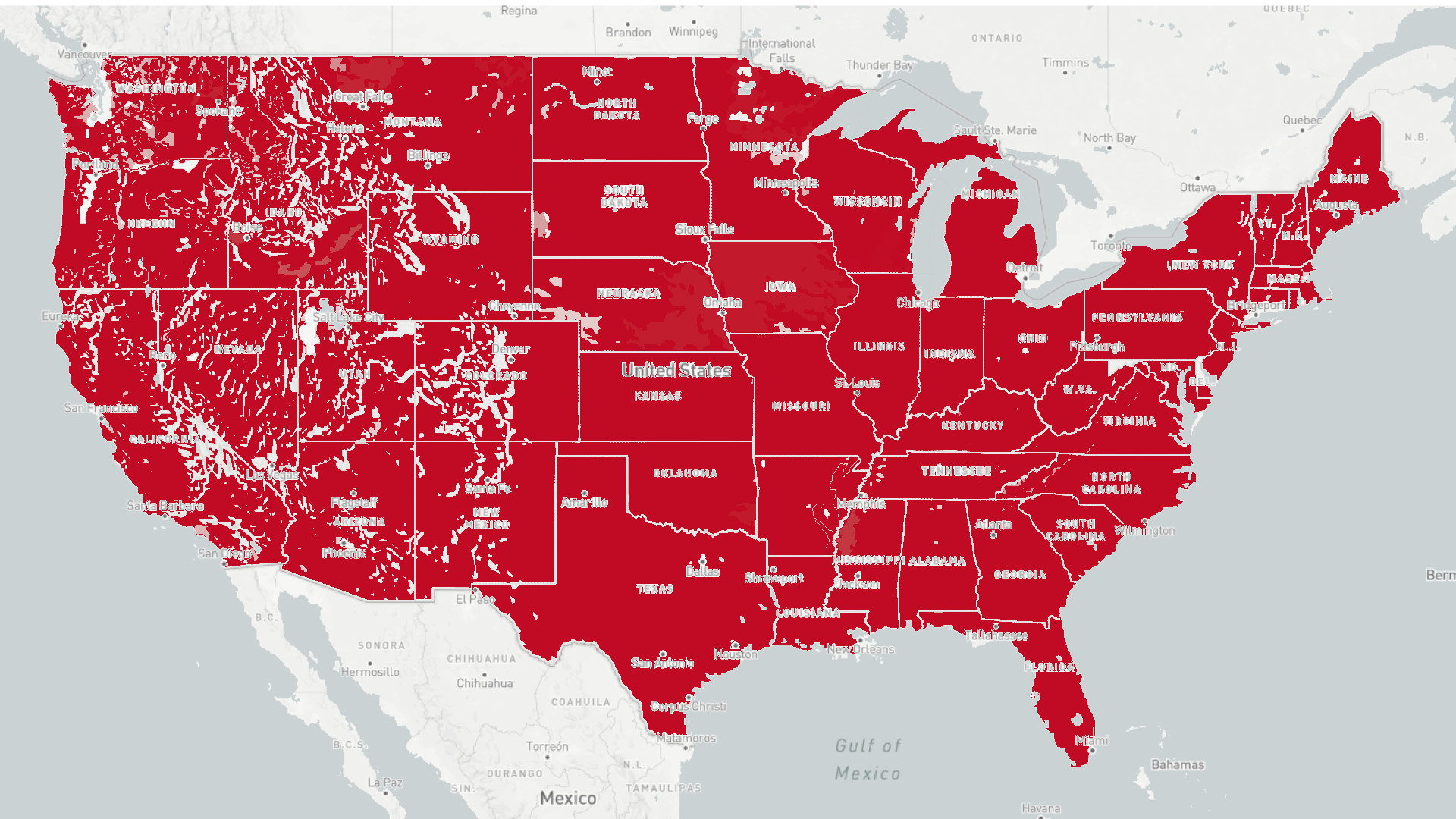

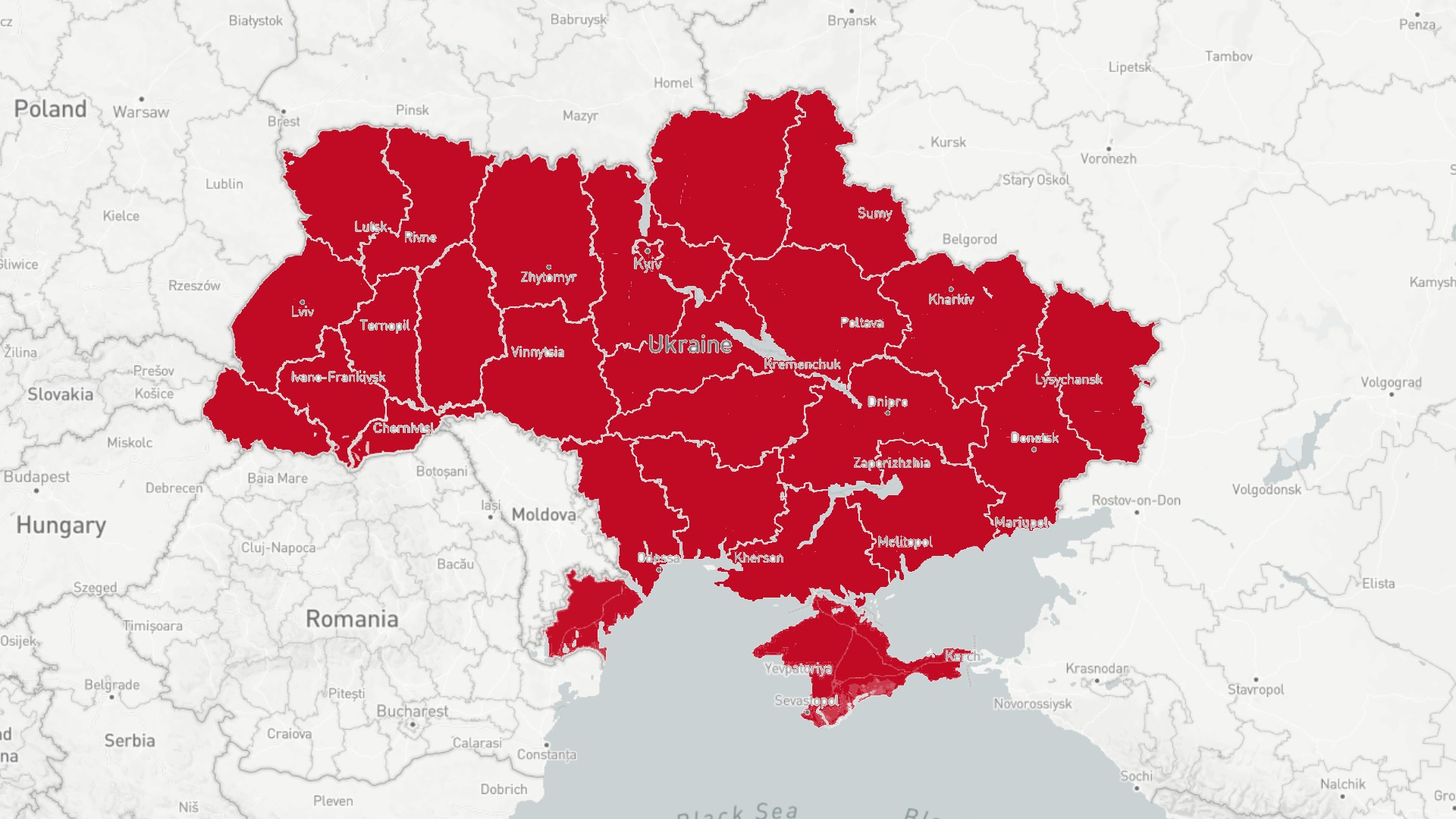

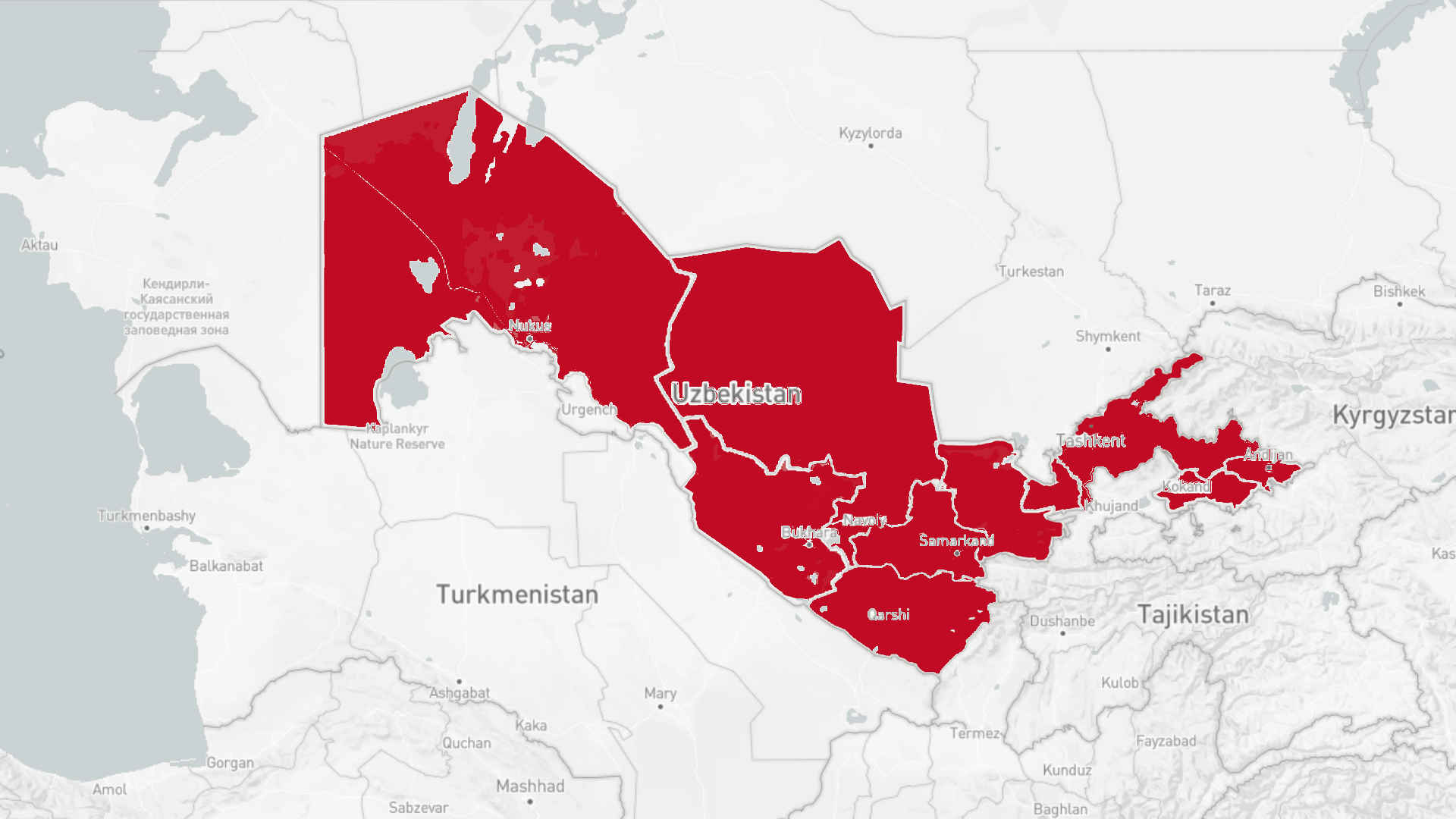

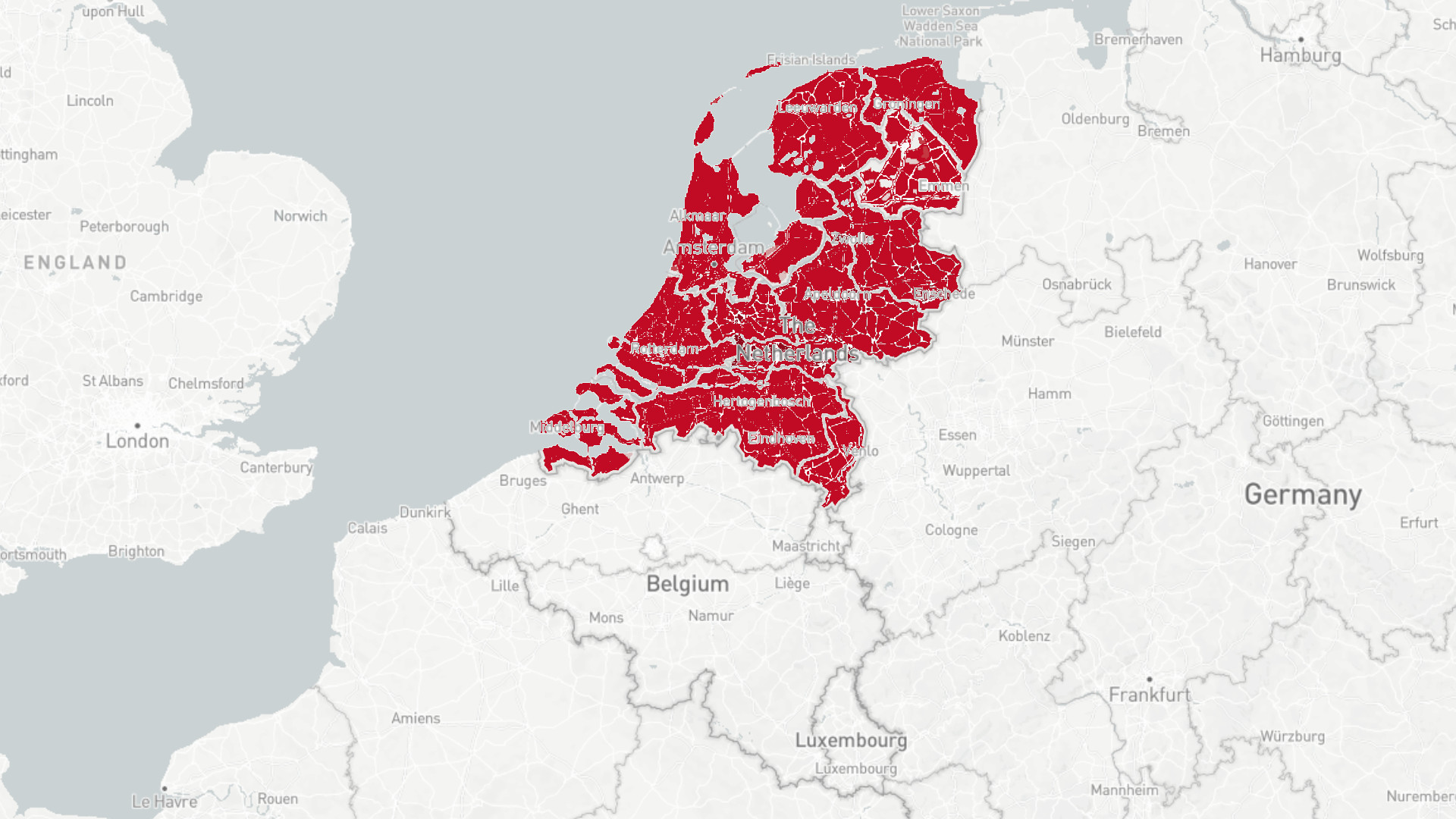

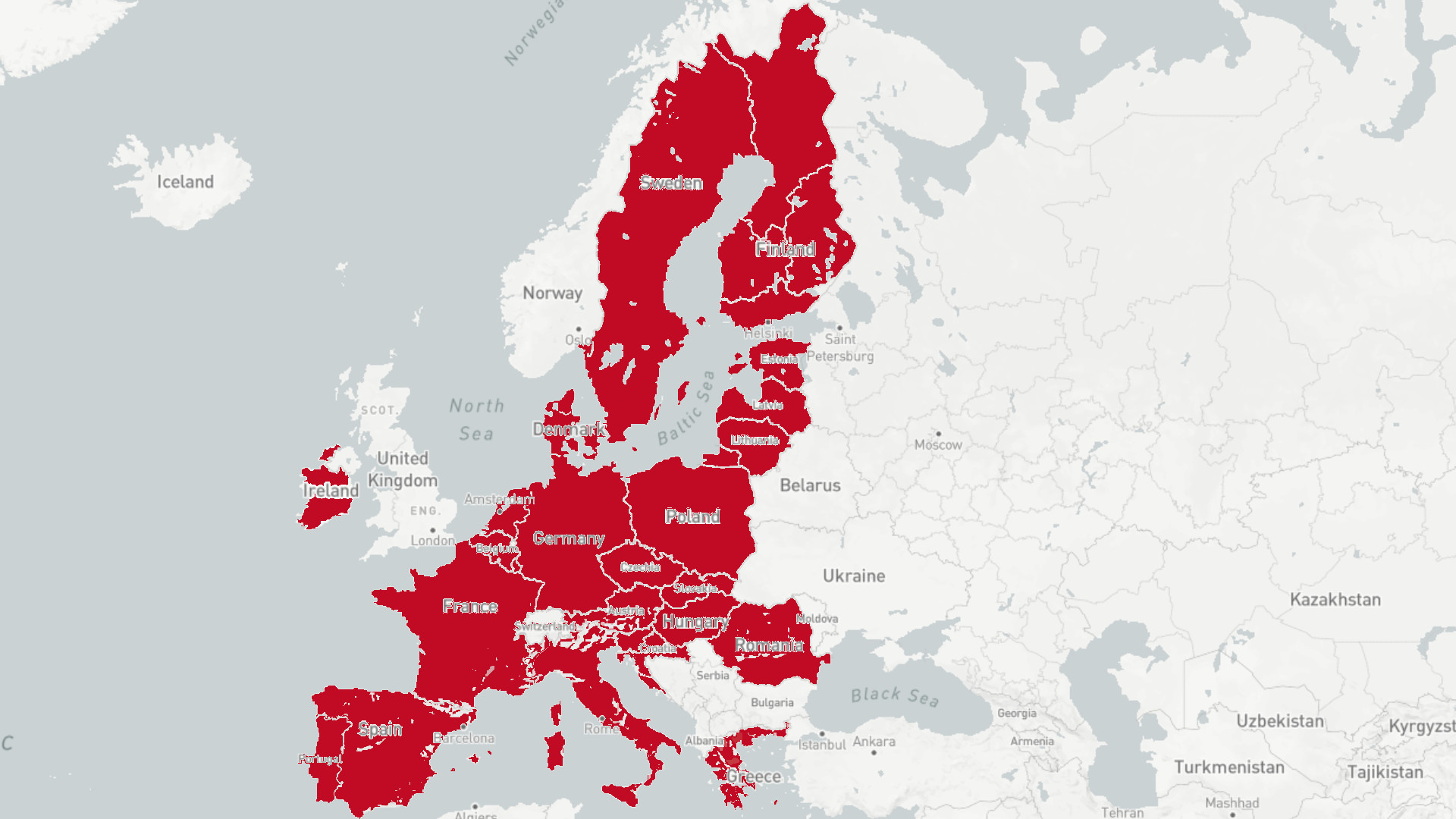

With 62 million daily users, the United States represents almost half (41 percent) of all accounts. In both America and the UK, one in five people is a Tweeter. The platform therefore plays a more significant role there than it does in other countries, such as Germany. Twitter is also widely used for entertainment. Many memes originate here, and are then shared on the other networks. Of the ten most popular accounts, eight are celebrities: Popstars like Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, etc. The remaining two are Barak Obama and Donald Trump.

The average Twitter user differs from the average American: 22 % of US citizens active on Twitter are more educated, more left-winged, and above all, more interested in current affairs than the average citizen. This is the result of several studies done by the Pew Research Center.

These studies also reveal a basis of Twitter's sociology. The accounts can be divided into two groups: the top 10 percent and the bottom 90 percent. The top 10 write 80 percent of all tweets, and have on average, twenty times more followers than the bottom 90 percent. As a conclusion, there are clear producers and clear recipients.

Twitter is the cinema of the present society. The majority sit back in their seats with a coke and popcorn, while footballers, musicians and politicians throw hashtags and at-tags at their heads. And in the middle of it all, journalists are also pulling along.

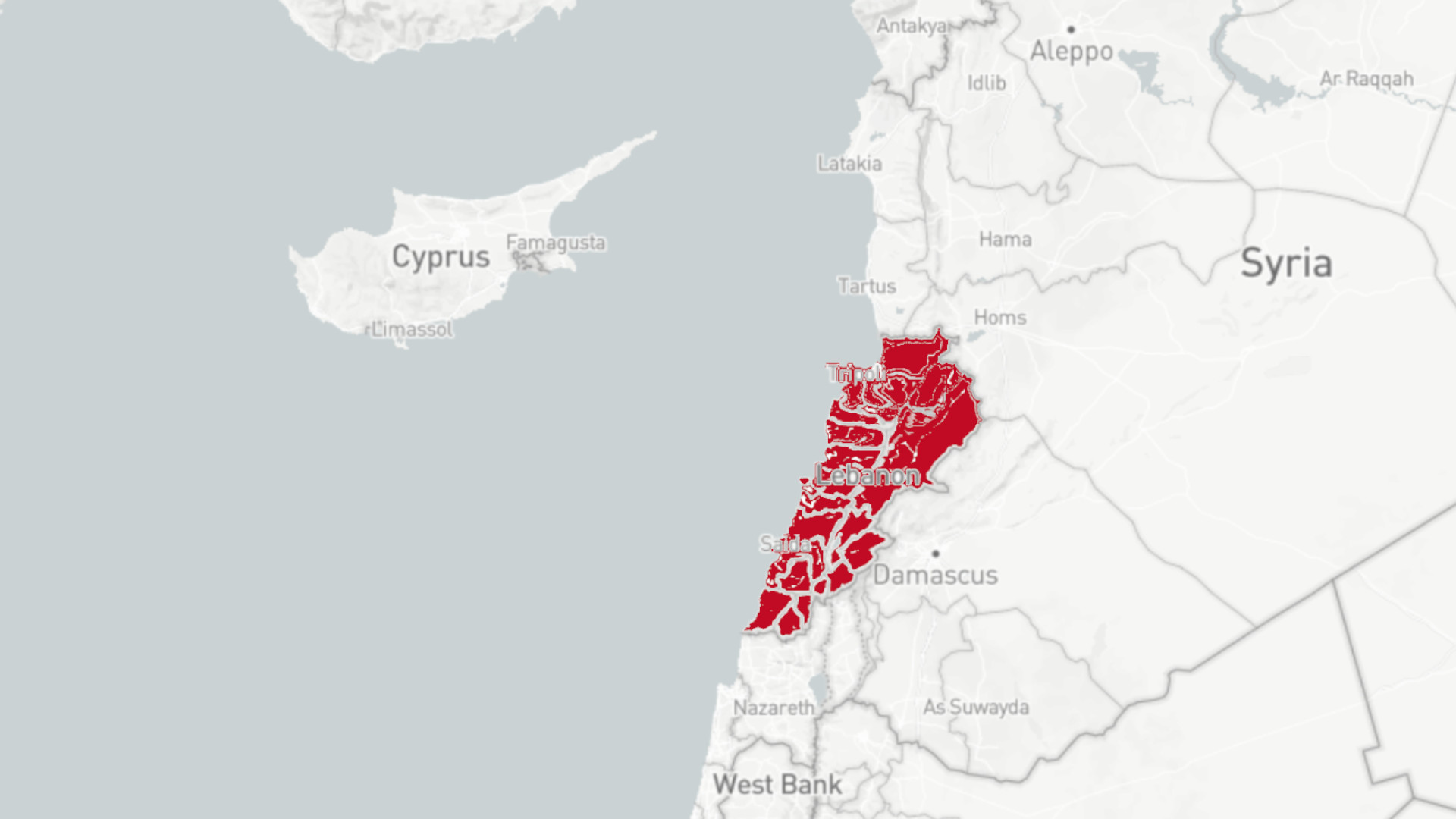

Journalists and their news agencies are responsible for a third of all tweets. Young, progressive journalists in particular are building their careers on their proactive Twitter accounts. They refute false statements from politicians, express their indignation at police violence, or they write about their everyday lives. Above all, they do not have to mince matters. This is a great advantage for Tweeters living in authoritarian states.

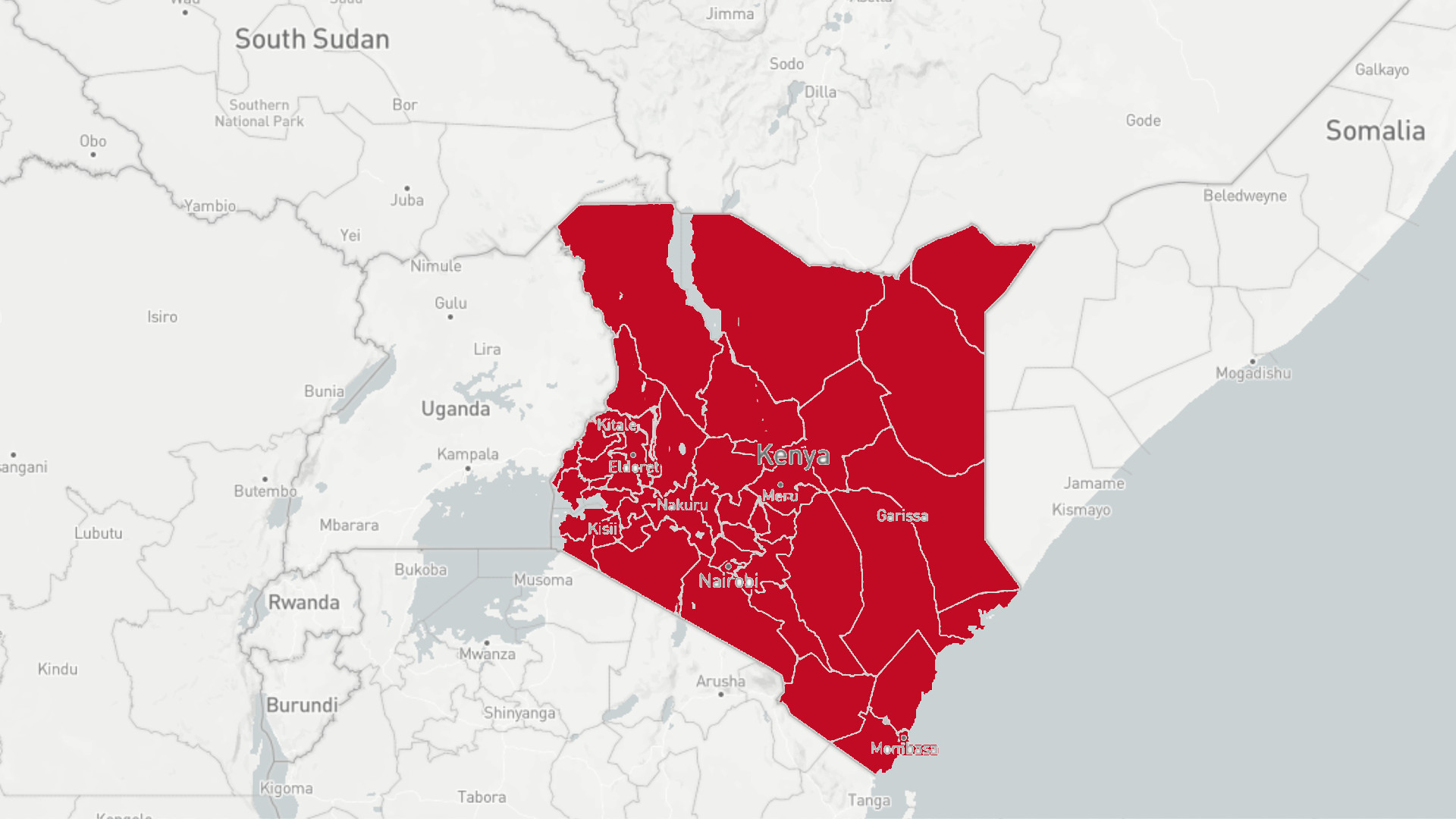

Atif Tauqeer is a Pakistani journalist. He is followed on Twitter by 123,000 people, a few thousand more than Margarete Stokowski, a young star columnist of the Spiegel. He is adamant that without Twitter, he could not work as a journalist.

He tweets daily about the political situation in Pakistan. For example, "Hey, I have an interview with the politician XY, what should I ask him?" His followers answer immediately and within a few hours, his list of questions is complete.

In theory, Tauqeer can tweet about anything he wants. However, the military tries to reinforce its dominance on the internet with fake accounts, which are regularly removed by the platform. Furthermore, Pakistan's blasphemy law is being enforced on social media to silence critical journalists. Tweets against the military, or the established religious order of the country, are considered dangerous. First, these journalists disappear, and later their arrest is officially announced. This is what happened to Matiullah Jan, who was kidnapped last month because of a tweet.

Twitter seems to be the last hope for the fragile freedom of the press. However, it is only superficially so. First and foremost, Twitter is driven by profit. The company could have been harsher on fake news from the outset, for instance on those coming from the US president. But why would they? Their profit is boosted by the symbiotic relation they established with the president. Donald Trump can shout his message to a world unchallenged by critical journalists, and in return, Twitter appears in every other media report from the US. This arrangement went well, until the chances of the president’s re-election began to slip. Twitter started to delete some of the false statements concerning Covid-19, which infuriated the president. Following these incidents, not much has happened. Twitter, like all social media, remains a hotspot for fake news.

"And yet the future of journalism will depend on Twitter," says Tauqeer. Pakistan has a rapidly growing number of Internet users, who will continue using their mobile phones to keep up to date. Moreover, it is extremely convenient for a journalist to have access to a platform where, with the help of a few characters and hashtags, he or she can get in touch directly with politicians. Normally, it would take days of phone calls to reach them.

"You cannot reverse the development of a technology. We just have to learn how to use it properly." And so, Twitter becomes a new tool in the journalist's survivor kit.