The Valley of Promises

At first glance, the Bisri Dam, officially called Lebanon Water Supply Augmentation Project, might seem just like any other big infrastructure project. Some want it, some don’t. There are talkshows, protests, petitions and campaigns from both opponents. But this is Lebanon. This is a long history of distrust and fear, of the people versus the political class. And it is also a history of failed infrastructure projects, false promises and questionable European engagement.

written by

Lisa Schneider

The Bisri Valley in its pristine condition. Activists want it to remain like this. (c) Roland Nassour

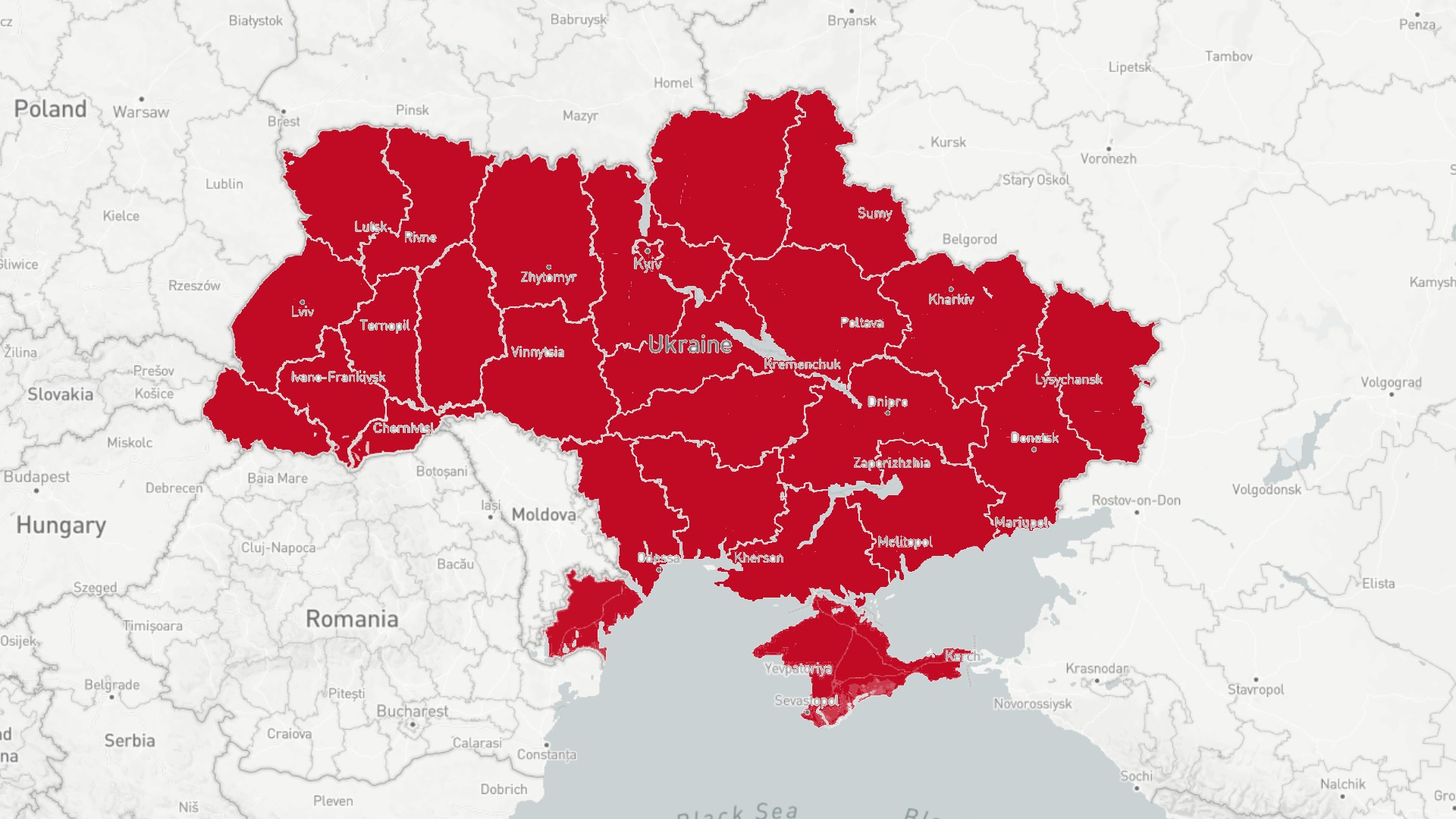

Beirut is a consuming city. It stretches far along the coast, to the North and South, blending into other towns and villages along the road, and to the East, pushing high up the mountains. Its overwhelming tempo makes one rush through the day, only slowing down in endless traffic jams and, for those who can afford it, in the many cafés, bars and restaurants that leave it buzzing day and night. Calmness is never an option. To find it, one has to leave. However, pristine nature is rare. A tiny country of just 10.452 square kilometres — the German state of Bavaria is about 7 times as large — and a population of approximately 6.8 million people, it is highly fragmented by settlements. One of those untouched spots is Marj Bisri. It is nestled between the Chouf mountains to the North and the district of Jezzine to the South, a picturesque valley, Lebanon’s most biodiverse region and historically gifted with the ruins of Roman temples, the old Mar Moussa Church and the remains of the Saint Sophia monastery. But there is a threat looming over the valley — or a chance, depending on the side one stands on: The Bisri Dam.

Minteshreen, an activist organization for social change, shares on Instagram: „Building the dam will result in 6 million square metres loss of natural areas, and agricultural lands, loss of biodiversity and the dismantling of over 50 historical sites.“ The World Bank, main financier of the project states: „(It) will benefit over 1.6 million people living across Greater Beirut & Mount Lebanon, including 460.000 living on less than $4 a day, who will have access to clean and improved water supply service without spending additional expenses on alternative water sources.“

At a first glance one might say: This is an old conflict. Some want preservation, some want change, some value nature, some value progress. However, Lebanon has a history of problematic and failed infrastructure projects, especially regarding water supply and dams — but not only that. On the fourth of August 2020, an explosion shook Beirut and subsequently the world, when tons of Ammonium nitrate, stored negligently in the port, caught fire and reduced Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael, Beiruts most lively districts, to rubble, killing 190 people, injuring 6.500 and taking the homes and jobs of many more. Marwan Solh holds a Master’s degree in Economics of Rural Development, and has worked in the field for many years. He says: „The issues regarding water dams are the same issues every government run sector faces: Mismanagement, lack of good governance, incompetence and corruption. The recent port tragedy is a perfect example of this.“

Lebanon, although one of the most water rich countries of the region still suffers from its shortage. To provide relief 13 dams have, until now, been built, spread all over the country. The oldest, the Qaraoun dam, fed by the Litani River, could be called the most successful one. It was created in 1959, and provides not only drinking water, but also electricity. But even though the dam is functional, problems have arisen on the Litani River. It is heavily polluted, undrinkable and carcinogenic. Litter lines it like weed. This is the „good“ kind of pollution, one that can be collected, filtered, removed. The chemicals are worse. Sewage, untreated. Industrial waste. Slaughterhouses relieving their unfiltered waste directly into the river. Years of neglect were supposed to end in 2016: The Lebanese government signed a contract with the World Bank over 55 million USD, for the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project. The project was destined to finish in 2023. Since then, nothing much has happened.

In June 2020 the World Bank issued a new rating for how well the project had been implemented — moderately unsatisfactory. Out of four project development indicators one had not moved forward at all, one barely, one about 15 percent, and one by roughly two thirds. The intermediate results are not better. Only 168 new household sewer connections have been built, by 2023 there should be 7300. No trash has been removed. Only 18 kilometres of new sewer lines have been constructed with an objective of 200 kilometres. Of the loan sum of 55 million USD, nothing has been repaid yet. There are two other projects, the Brissa and the Mseilha dam, that have remained largely unsuccessful. Tony Nemer, Assistant Professor of Geology at the American University of Beirut, states: „The Brissa dam never collected the planned amount of water.“ And The961, a Lebanese online news publication adds: „The Mseilha dam failed to meet its purpose“, as water keeps leaking out of it. Piquantly, both dams have been constructed by the same company, BATCO, which Financial Prosecutor Judge Ali Ibrahim even filed a complaint against for wasting public money.

For both projects a German deep mining company called BAUER was employed as a sub-contractor. BAUER’s head office is located in Schrobenhausen, a small town about an hour north of Munich. While no direct failure can be attributed to them, their employment raises the question, to which extent European companies can be held accountable for mismanagement in the projects they engage in. And BAUER is not the only European enterprise involved. The Mseilha dam was partially constructed by Maltauro and Gruppo Simonetti, both headquartered in Italy. The latter also worked on the Brissa dam. For Mseilha, Coyne & Bellier, a French company had executed the consultation process. Meanwhile, the World Bank has come to the conclusion that the Lebanese government needs to step up and make sure that failures like these will not happen in Bisri. While the World Bank had already agreed on providing a 617 million USD loan, it was postponed until the fourth of September, awaiting the government’s measures. Currently the deadline has ended. The Lebanese government has not provided the required information. The loan will be redistributed. And the Bisri Valley will remain the oasis of calmness it was.