Perpetrator Therapy

Learn to unlearn

written by

Katharina Wellems

The number of women finding the courage to speak up about their experiences with domestic violence or sexual abuse is rising steadily. The #metoo movement has encouraged many affected persons to come forward and to name their offenders – mostly men. But what happens to those men? Are they condemned to being labeled as ruthless criminals? Or is there a way to give them the opportunity to start anew? Perpetrator Therapy tries to give those offenders a second chance.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one third of women who have been in a relationship report that they have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner at some point in their lives. This number is expected to rise dramatically due to the lockdown caused by the Corona pandemic. Nevertheless, more and more women speak up against these crimes. „Women won’t put up with this anymore“, says Gerhard Hafner, #heforshe-ambassador for the UN. Women are uniting their strength, building networks and aid organizations, and are empowering each other. But where are the men these women are standing up against? Perpetrator therapy is trying to help them to change for the better.

Offenders must abandon violence

“The aim of perpetrator therapy is non-violence”, says Torsten Brakemann of the Hamburger Gewaltschutzzentrum. Furthermore, it is an integral part of the protection of victims. Perpetrator therapy underlies a positive human image: Behaviour can be learned, but also unlearned, says Julia Reinhardt from the Bundesarbeits-gemeinschaft Täterarbeit Häusliche Gewalt.

The core of perpetrator therapy, is anger management training which takes place in a group setting. Offenders learn to stop the violence, and learn to have empathy for their victims instead. The concept originates from the United States. John Hamel, social worker in San Francisco and head of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Providers, explains that the treatment of domestic violence was largely taken over by the women’s movement in the 70’s during the second wave of feminism. Feminists and battered women’s advocates joined together to help pass laws against spousal abuse and violence against women in general. Christopher Murphy, professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, adds that in the past, people who committed abuse did not face repercussions for their behavior, and many did not consider it a crime. Thus, when the initial counseling programs were developed, the goal was to hold people accountable. The logic was, that if the law was not going to penalize perpetrators for their abuse, counselors would somehow be able to punish them for their actions. This concept reached Germany only fifteen years ago. The Bundesagentur für Gesundheit, (BAG), was founded in 2006 as an umbrella organization, which sets the framework for most organizations in Germany today. At present, the BAG is made up of about 60 to 70 organizations.

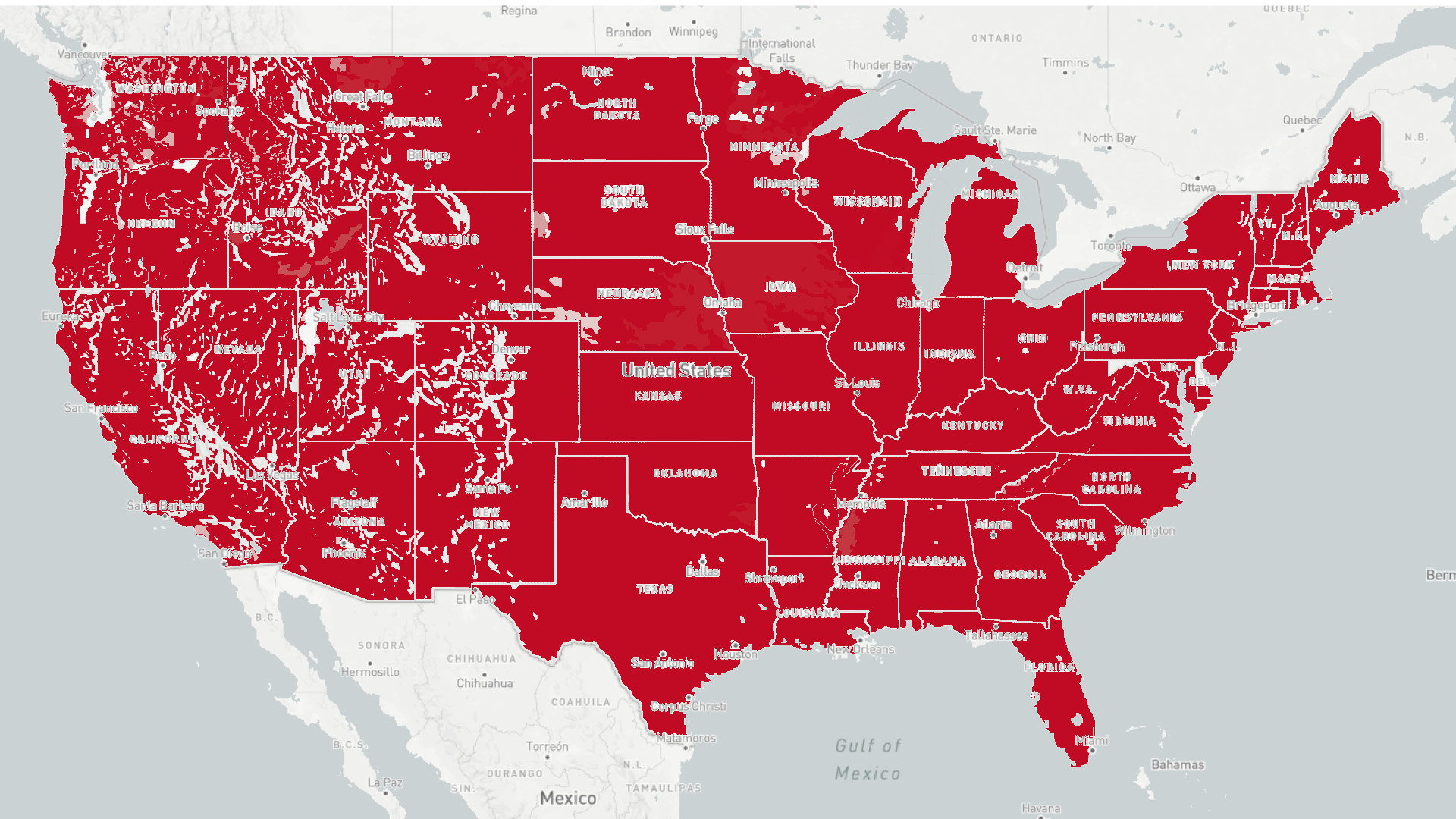

In contrast to Germany, perpetrator therapy in the United States is not organized in such a central way: „Each state has its own regulations and processes - most have standards or guidelines for abuse intervention programs”, states Christopher Murphy, whose research focuses on emotional abuse and physical violence. The funding also differs greatly from German organizations. While the government in Rhineland Palatine pays for 90 percent of the therapy programs, most programs in the USA are funded through direct pay client fees. Some costs may be supplemented through various state grant programs, or private foundation grants obtained by the organizations that offer these services, but Murphy does not know of any state that pays directly for a perpetrator therapy program.

„Being an offender once is enough“

Perpetrator therapy builds upon a broad understanding of violence: „One does not need to hit someone, to apply violence. For us, violence starts much earlier than for criminal law“, says Julia Reinhardt. Even a verbal comment such as: „Don’t you dare leave the house dressed like this“, can be counted as violence.

Nevertheless, perpetrator therapy is not suitable for every offender. The BAG sets harsh exclusion criteria: Criminals such as stalkers, or other such offenders, who do not admit to their crimes, and have no sense of wrongdoing, will not be included. Alcohol or drug addictions are excluded as well because addiction therapy would be more suitable for those offenders, says Julia Reinhardt. Sex offenders are also excluded, unless the sexual violence takes place within a relationship. It does not matter how many times an offender used violence against someone to be suitable for perpetrator therapy: „Being an offender once is enough“, says #heforshe ambassador Gerhard Hafner.

Torsten Brakemann works with violent offenders in Hamburg, Germany. He reports that men from all social classes seek his advice: „From journalists and lawyers, to unemployed persons – they’re all there“. John Hamel from San Francisco also cites studies which show that the perpetrator’s origin has no influence on the effectiveness of the therapy.

The average age of violent offenders differs greatly. According to Gerhard Hafner, offenders are between the ages of 18 and 80 years old. Nevertheless, the majority are between 20 to 40 years old. This is because the time when people often start a family has proven to be highly conflictual. All offenders have one thing in common when they enter the program: „Nobody actually feels good“, says Julia Reinhardt. „Most come with severe psychological strain, and say they don’t want to be violent anymore “. However, only a third of all offenders reaching out to German perpetrator organizations do so of their own accord. Two thirds are obligated to do so, due to official instructions from justice, or are advised to come forward by the police or youth welfare offices. „Many offenders don’t want to participate, but still show up. Many offenders should participate, but don’t show up at all“, Julia Reinhardt sums up.

Identifying abusive behavior

To reach out and ask for help is often the hardest part for perpetrators. But the actual work begins afterwards. „They are not cured only because they show up at our counseling center“, says Torsten Brakemann. In the first interview, social workers investigate the offender’s situation. Together with him, they figure out if the offender is suitable for therapy. Whether the offender confesses to his crime is crucial for this decision. The actual therapy in the U.S. as well as in Germany, often takes place in group settings. Together with other offenders, perpetrators work on strategies of how they can prevent violent behavior and reduce aggression. It is important for them to learn how many shades violence can have: „Men must train not to change physical violence into psychological violence instead“, reports Gerhard Hafner. However, some perpetrators are too disruptive in a group setting and need individual counseling as well. Therapy programs in the U.S. take between 16 and 52 weeks. The BAG in Germany demands that programs entail at least 25 sessions over a period of six months. John Hamel states, there are five important goals offenders should achieve in therapy. They should learn to overcome stress and to manage their emotions, understand that violence is not helpful, identify unhealthy or abusive behavior, improve their communication and conflict resolution skills, and overcome past trauma and mental disorders.

“Men have to move mentally”

It is hard to say how successful perpetrator therapy is. There is only one study existing in Germany, says Julia Reinhardt. But according to this study, the programs seem to be effective. Brakemann however, reports that only half of the participating offenders stay in the program until the end. Dr Hamels research suggests that group size should be kept small. “It is particularly important that offenders understand therapy as an offer for them, and not against them”, says Julia Reinhardt. During therapy, physical violence decreases rapidly. However, it differs with psychological violence. It also decreases, but often does not completely vanish, because many offenders find it difficult to see that violence means more than just beating another person. Brakemann experiences time and again that some offenders can’t be helped after all: „There are men who remain intransigent”. Christopher Murphy has worked in perpetrator therapy for over 25 years. The professor of psychology finds, the stronger the bonds that you can foster in the group, the more likely people are to stop their violence. For him, empathy, support, connection and alliance can have a great effect on the rate of success.

Christopher Murphy notes that perpetrator therapy itself must adapt to feminist progress. According to him, it is necessary to update the vocabulary used in therapy in order to be more conscious and aware. He uses a feminist approach in his work to address some of the thinking patterns, and to help men understand why violent behavior cannot be accepted. Men in perpetrator therapy often have a hard time adapting to the rules of the new, more feminist world. „Change always leads to uncertainty “, says Gerhard Hafner: „But men have to learn to move mentally, because women have been doing it all along.”