A Letter to the President

Germany & Poland | 2020

written by

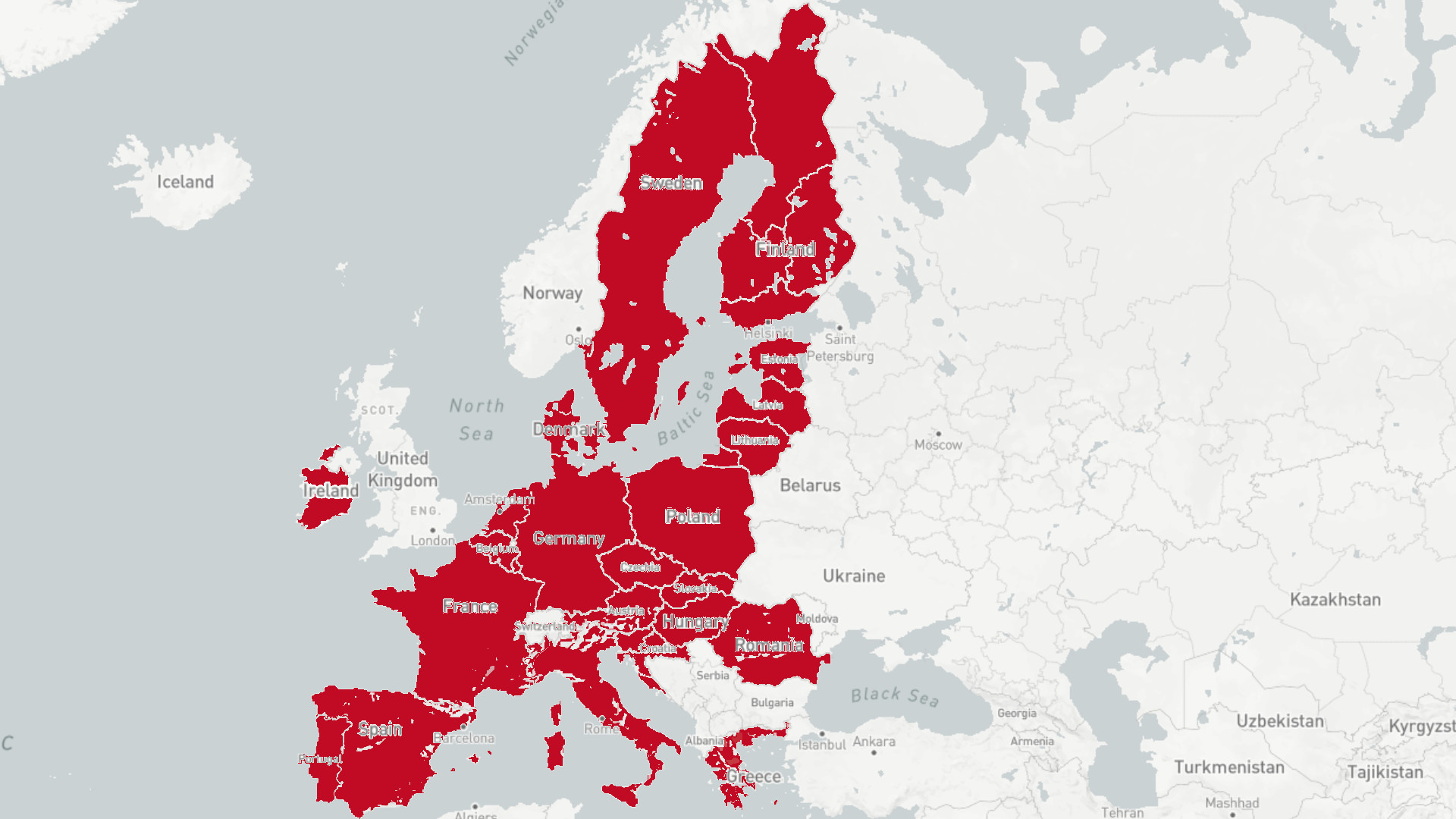

Voting in times of an international pandemic isn’t easy. On the one hand, democratic leaders must be legitimized by their citizens. On the other hand, health risks need to be limited. One possibility for an election that keeps citizens safe, is voting by post. Acceptance of postal voting depends on political traditions and trust.

Warsaw, June 2020. Andrzej Duda was reelected as Polish president. In the runoff, he received 51 percent of the votes. It was a close finish to an unusual election. Initially, the election date was set for May 10. Due to the corona pandemic, it wasn’t possible to hold normal elections. While the opposition wanted to postpone the election, the leading PiS-party wanted the election to be held on the appointed date, but exclusively by post. In order for this to be legally possible, the electoral law needed to be changed. In the days following up to the election, this seemed impossible to achieve. The draft was criticized heavily, not only by the opposition, but also by international institutions such as the organization of human rights of OSCE, and members of the governing coalition. According to critics, the changes would have been too numerous, too profound, and too fast. The government was forced to give in, and the elections were postponed.

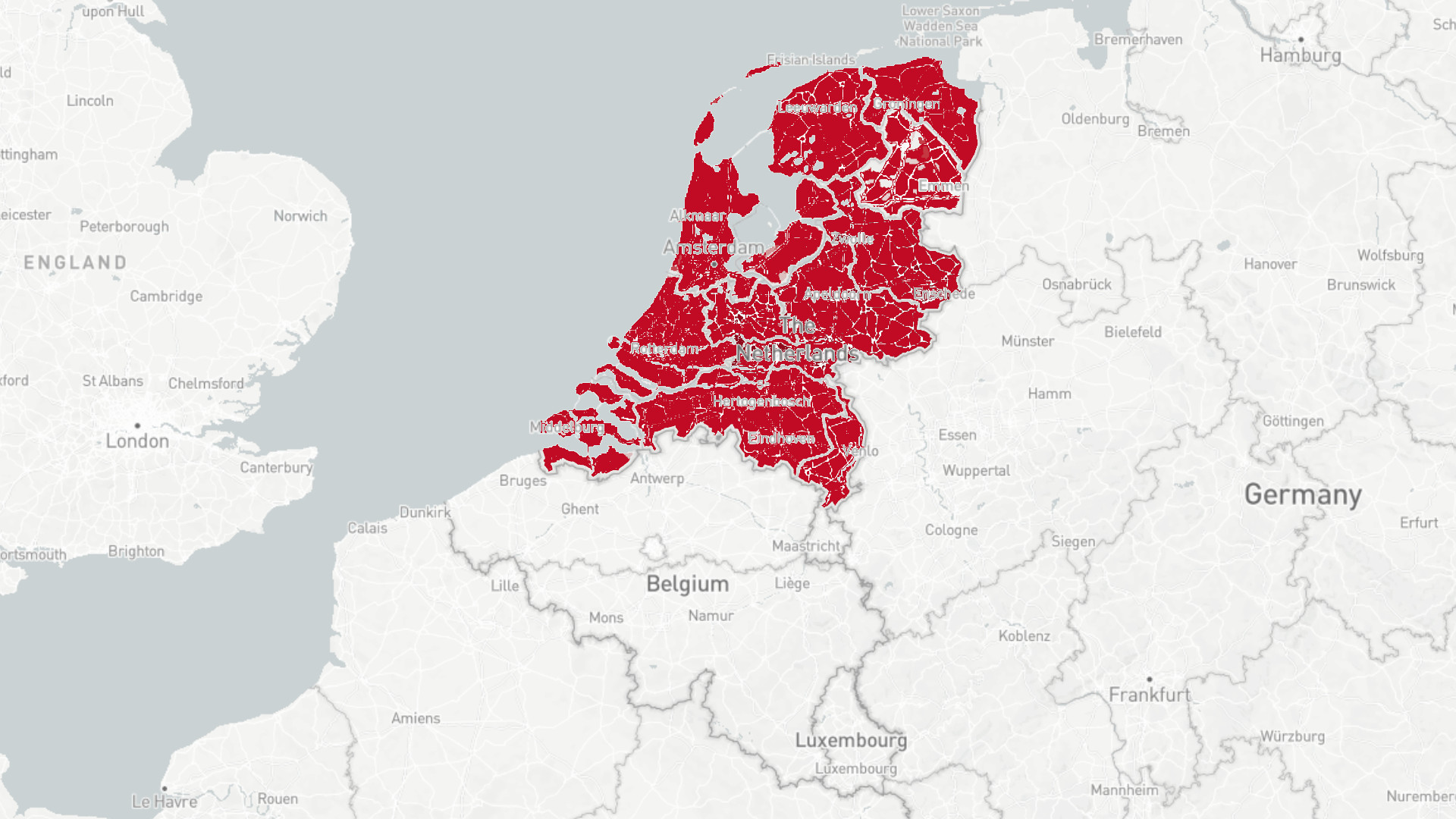

Munich, March 2020. The Bavarian government decided to hold elections in 16 Bavarian regions exclusively by post. It was a decision the government made, based on the Infectious Diseases Protection Act – without any legitimization by the parliament. Only four days before the elections, the Bavarian parliament passed an urgent procedure act to change the electoral law. Otherwise, the election could have been contestable. This case barely made the news. Germany it seems, in contrast to Poland, has a very trusting and accepting attitude towards postal voting. But how can a voting technique trigger a state crisis in one country whereas in another, nobody even cares?

“It has to do with habituation and experience”, says Bastian Sendhardt of the German Institute of Polish Affairs. Whereas postal voting has been allowed in Germany for almost 60 years, it was only introduced to Polish electoral law in 2011 – but only for people with disabilities or Poles living abroad. In 2014, with the hope of achieving a higher turnout, the leading coalition PO introduced postal voting for all Polish citizens. But the expectations were disappointing. Only several thousand people voted by mail. In 2019, ruling party PiS limited electoral law again, arguing that it is prone to voter fraud. From this point on, only people with disabilities were able to vote by post.

However, only one year after the limitation of postal voting in Poland, the PiS-coalition did a U-turn during the Corona crisis, and tried to hold to the initial election date by introducing postal voting to the electoral law again. Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska, presidental candidate from the opposition party “Civic Platform” PO, called this “a coup”. For her and other critics, postal voting seemed to be a trick to keep Andrzej Duda and the leading PiS-coalition in power.

Political aims of parties always have to do with the preservation of power, Bastian Sendhardt from German Institute of Polish Affairs explains. This time, it seemed important to hold on to the initial voting date, as Andrzej Duda had a good chance of winning, according to the election polls. His popularity could have decreased, if the Corona crisis caused economic problems over time. Those elections were not only about an electoral technique, but mainly about the preservation of power, Sendhardt says.

Not all politicians in the leading coalition supported the idea of postal voting. Jarosław Gowin, Polish deputy Prime Minister, resigned because he didn’t want to vote for the electoral law. Instead, he wanted the election to be postponed for two years (which can be seen as another form of power prevention). However, after a long and difficult process, the Polish presidential elections were neither held on the initial election day, nor were Polish citizens voting exclusively by post. As the pandemic situation had relaxed, a new amendment allowed both postal and ballot voting. Still, Duda won the elections, and Polish people continued to be critical of postal voting: Of more than 20 million voters, only about 593,000 people voted by post, less than three percent.

In Germany, within the last several years, the number of postal votes increased from election to election. During German parliamentary elections in 2017, more than one in four voters were sending their votes by post instead of going to the ballot box. During the first elections in 1957, it was less than five percent. However, not only one year ago, voting by post had also been the subject of a controversial debate in Germany. In an interview with Funke Mediengruppe on the European elections in 2019, Bundeswahlleiter Georg Thiel showed concerns about the increasing number of postal votes in Germany. Thiel said, that for the German constitution, ballot box voting was the standard. Postal voting on the other hand, could violate democratic principles regarding the electoral secret and equality.

Harald Schoen, political scientist at University of Mannheim considers postal voting in Germany more as a technical question. “Postal voting always comes with the weighting of two values”, he says. “The German Supreme Court in a principle decision found that postal voting is critical, especially regarding the election secret. On the other hand, however, the postal vote can fulfill one democratic principle even better: The principle of general elections.”

Due to the Coronavirus, not only the election in Bavaria, but also the elections for next parliament, could be postal elections. In May, the newspaper “Rheinische Post”, published the plans of the German government to hold the Bundestag elections in 2021 exclusively by post. In contrast to Poland, the criticism by politicians, citizens and media remained quiet.

Schoen explains, “In the situation of an international pandemic, postal voting could legitimate political power without any health concerns. It could even be necessary to exclusively vote by post in this specific situation, because any postponement could seriously violate the elections as an institution of recurring legitimation of power”.

So, is it all just a matter of perspective? Is it really so simple? Germany, with its high acceptance of this method and its frequent use, should not be seen as the norm in the international comparison, says Bastian Sendhardt from German Institute of Polish Affairs. “Postal voting is controversial, not only in Poland, but overall, in international political research.” The potential manipulation must be seen as a serious argument. “The international trend regarding postal voting is to use it rather as an exception”, Sendhardt says. However, if an international pandemic is a reason for such an exception, is a question that will probably be asked often during the next months all around the world.