Losing the information war?

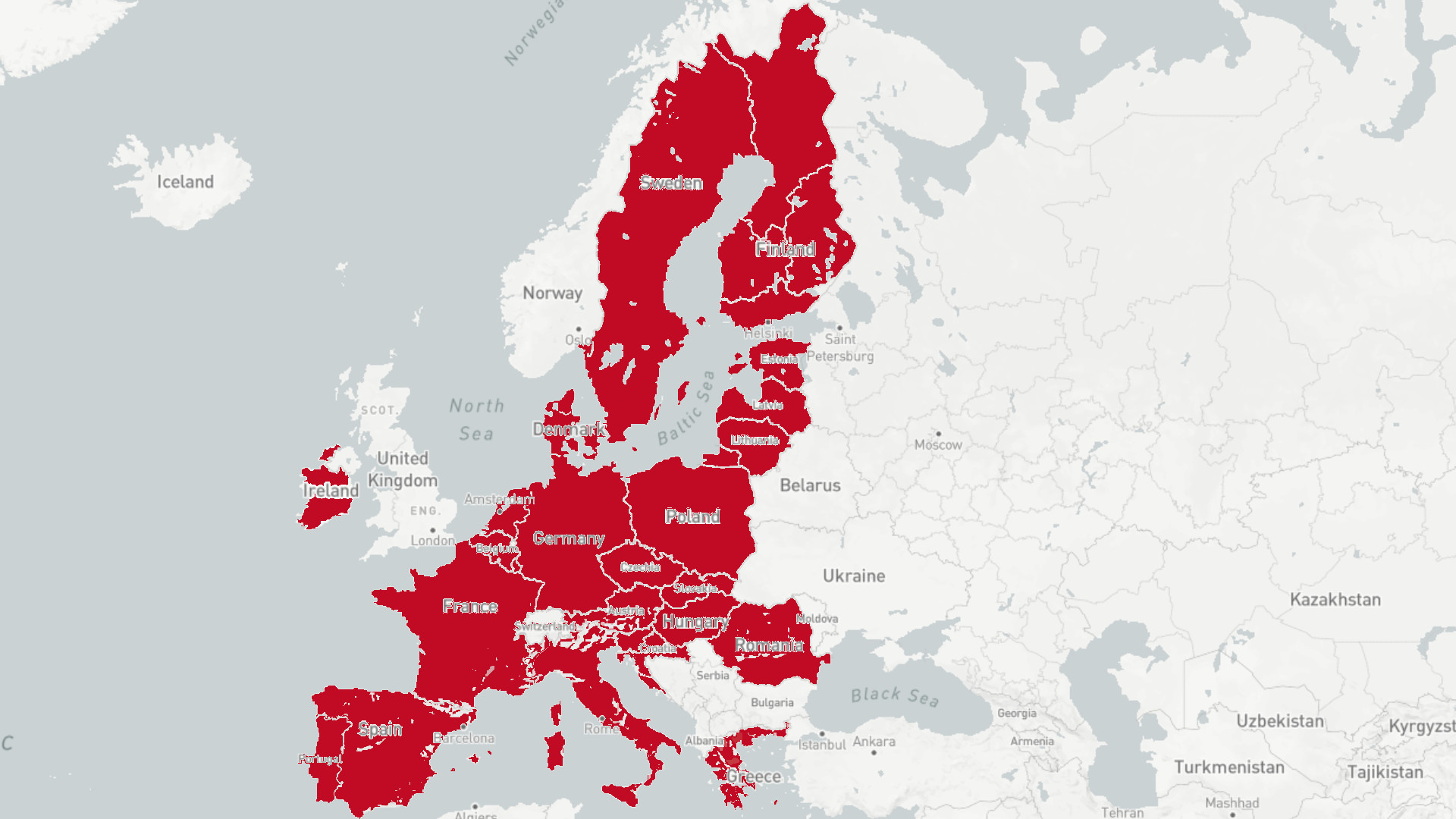

Whether it’s interference with elections, propaganda stories, or carefully orchestrated narratives to undermine the reputation of entire nations: Russian disinformation in the 21st century appears to be one of the greatest threats for peace and safety around the world.

written by

Jana Ballweber

Each year, a report is released from the Domestic Intelligence Service in Germany. National media mostly reports whether the focus is on left or right-wing extremism. Or perhaps even Islamic extremism? Some consider it to be an indicator for which topic becomes top priority on the political agenda for Home secretary Horst Seehofer.

Quite far down in the aforementioned annual report, at page 282 out of 388, exists a topic which concerns Germany’s national security, but is widely ignored by the public: the activities of Russian intelligence services. The report states: “Besides espionage activities, Russia is striving towards influence on the political and the public opinion in Germany in the sense of Russian politics.” Several Russian actors, not only intelligence personnel, seem to be trying to tear apart German society, support extremism, regardless of its orientation, and to undermine the trust of the people in their political systems, their allies and their media.

The intelligence report strongly emphasizes the important role of online news channels like RT Deutsch or the news agency “Sputnik”. Political disinformation is largely found on platforms such as these. For Germany, they focus on topics where small parts of the population have a populist, radical or conspiracy agenda, like the Coronavirus or migration, and feature their protagonists. A famous example is the physician Wolfgang Wodarg who gained attention during the SarsCov2-pandemic with his downplaying statements about the virus. If fewer people believe the official and scientifically proven facts about the pandemic, then trust in German politics in general is weakened.

Disinformation: a geopolitical instrument

In doing this, Russian interest groups attempt to weaken the German state, the European Union and NATO on a geopolitical scale. To keep democratic and civilian movements inside Russia quiet, Russian president Vladimir Putin wants to reconquer the status of a superpower the Soviet Union once had for modern Russia, as the German author and expert on military, Yvonne Hofstetter, explains in her book ‘The invisible war’: “Putin fears an uprising of the Russian people because of the predatory behavior of the Russian elites and the stagnating economy. He is afraid that protesters would overthrow the government in Moscow like the Arabellion 2011 or the Euromaidan 2014, so he started to stimulate Russian restauration. He justified the narrative of Russia as a superpower with a whole lot of nationalistic mythology.” An us-against-them, Russia against the Western hemisphere, should work not only with the Russian population, but also with critics of the USA, NATO and the European Union.

Another goal the Russian administration is trying to achieve in Germany and other countries of the EU, is to incite protests against the EU sanctions on Russia. The country is suffering economically, and hopes to influence public opinion in Germany in their favor to create public pressure on the German government.

The sanctions were introduced after the annexation of Crimea, and the ongoing war in Eastern Ukraine. Unlike in Germany or Western Europe, Russian disinformation in former Soviet republics like Ukraine, doesn’t only cause a split in a nation’s society or weaken the trust in political and public institutions. It is more a question of survival for the people living in Ukraine, and the nation itself.

Tailored narratives for each country

IPeter Pomerantsev, a scientist from London School of Economics, analyzed Russian disinformation in his paper “Winning the information war”. He is convinced that Russian actors tailor their disinformation to specific countries. For Germany, he mentioned the story of the Russian girl Lisa, who allegedly was raped by migrants in 2016. The story turned out to be false, being both a mixture of lies and misunderstandings. However, Russian media was happy to publish the story because it fit with the German public discourse about present immigration issues, and was mainly led by populists like the right-wing party ‘Alternative für Deutschland’. It was seen as a story which was able to get people to be increasingly insecure, and even furious about Merkel’s migration policy.

For Ukraine, Pomerantsev found different strategies: “In Ukraine, Stopfake.org has identified two major narrative ‘themes’ used by Russian disinformation. The first interprets the Euromaidan protests as a coup d’état in which a Western-backed junta seized power from Ukraine’s rightful rulers. […] The second attempts to define the emerging democratic regime in Ukraine as ‘fascist’.”

NGO against Russian disinformation

The NGO ‘Stop Fake’ mentioned by Pomerantsev, is run by a Ukrainian fact checking group. Pomerantsev relied on the group’s work of checking Russian disinformation. The organisation started the project when the first soldiers appeared in Ukrainian territory. They couldn’t officially be assigned to a country, but were suspected to be Russian. The journalists noticed that the disinformation Russia was spreading about the Ukraine had a serious impact on society, and unsettled many people in the Ukraine and abroad. There is a long tradition of Russia, or in those days, the Soviet Union, denying that the Ukraine was even a state, an independent nation. Instead, until recently, they saw the Ukraine as a part of Russia.

In addition to their own website stopfake.org, the group also works with Facebook for fact-checking Russian propaganda on the platform. Were there really fascists on Maidan? Did the United States initiate and finance the uprising to cut the bond of the old Yanukovych regime and the Russian state? Most likely not. But there were times when it was difficult to tell what was true, and what was propaganda.

Negative impacts on critical journalism

Even today, it can be difficult to differentiate between the two. Journalism in the Ukraine has lost its ability to differentiate throughout the many years of war. Even the slightest criticism towards the Ukrainian government, or the at times, nationalistic approach when covering the war zone can result in a journalist being called a ‘Kremlin agent’. A difficult starting position for objective and independent journalism.

Recently, even ‘Stop Fake’ itself hit international headlines. Ukrainian journalist Katerina Sergatskova publicly criticized the NGO because one member, Marko Suprun, was photographed with a nationalist musician who denies the Holocaust. Sergatskova told the New York Times that she had to flee from the Ukraine because of death threats following her reporting. ‘Stop Fake’ confirmed the death threats against Sergatskova, but also released a statement to deny the accusations.

Again, it is hard to get an idea of what is right and wrong. Keeping in mind the narrative of Russian disinformation that the Ukrainian state mainly consists of fascists, it could easily be another accusation to simply discredit the fact-checkers. The photographs exist, but do they automatically make Suprun a supporter of radical views? For an outside observer, it is almost impossible to decide. The New York Times cites a critic who denies ideological links between Neo-Nazis and ‘Stop Fake’, but “[doesn’t] think that they are nonpartisan”. On the other hand, Ukrainian journalists like Otar Dovshenko criticize the initial article from Sergatskova as “just attracting attention”.

The story seems like a symptom of the whole information mess. A war is going on in the Ukraine, with over 13.000 people dead. International media is loudly reporting on a quarrel between journalists about the problem of the far right in the Ukraine. It is undeniable that the problem exists, but the focus of media attention is not representing the distribution of seats in parliament, or the public opinion. The case suggests that Russia partially got what it wanted: public distrust and confusion among readers and journalists in the Ukraine, Germany and around the world.