Free Speech via lottery win

Uzbek Dilshod Asadullayev had to leave the continent to finally publish articles about his homeland.

written by

Janek Kronsteiner

When Dilshod Asadullayev first arrived at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in early 2016, all stores in New York City were closed. A harsh blizzard had buried the whole state under a thick cover of snow.

“You couldn’t even see the cars under the piles of snow,” Dilshod said.

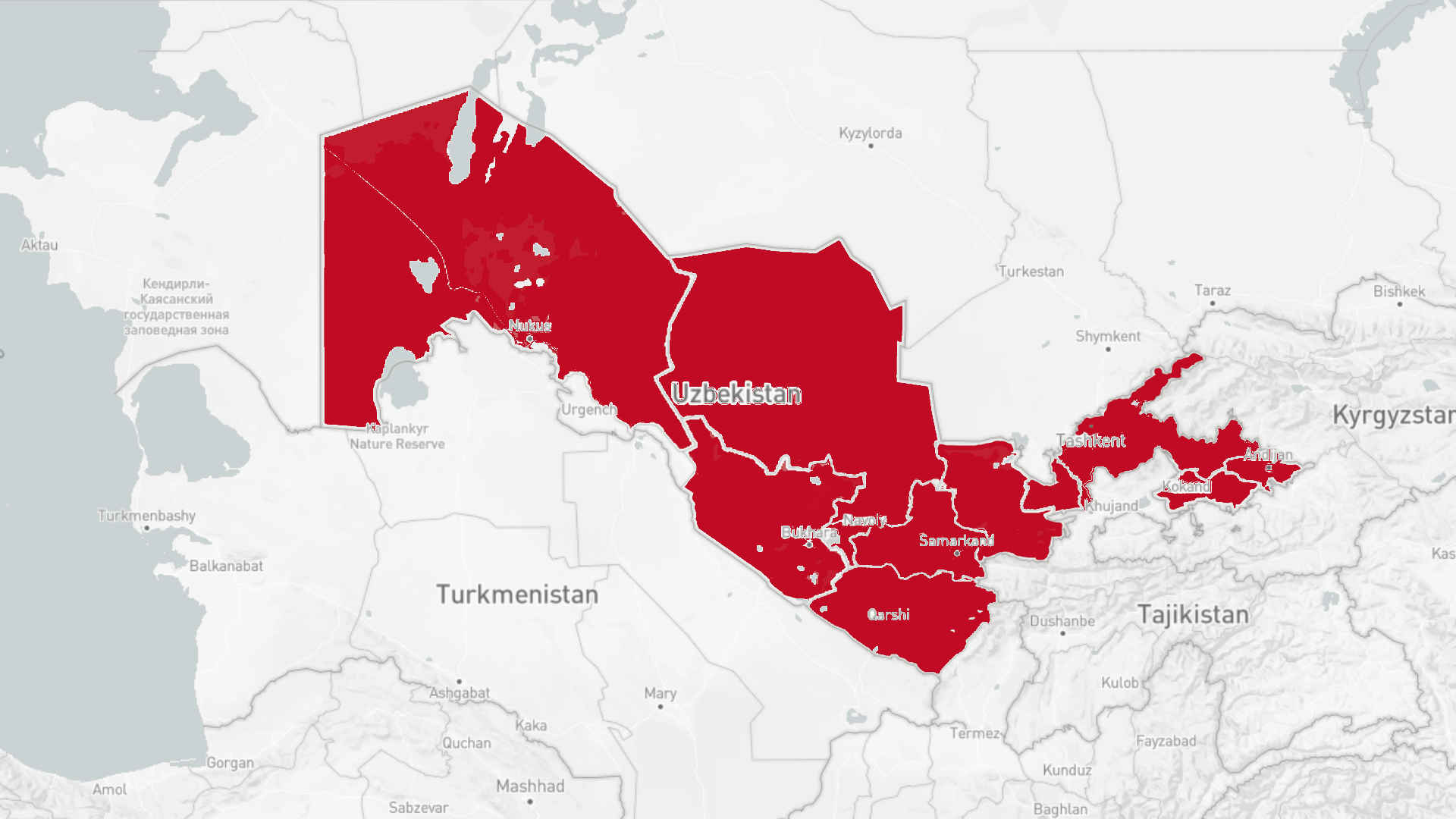

In his homeland Uzbekistan, Dilshod had never heard about the severity of North American winters. Today, the Uzbek people are well informed even about the COVID-19 outbreak not just in their region in Central Asian but also in New York. To a large extent, this is thanks to the work of Dilshod and his Uzbek language social media team at the “Voice of America.”

When Dilshod was born on April 3, 1981, the idea of stepping foot on American soil was just a fantasy. Raised in the province of Tashkent, not far from the Uzbek capital of the same name, he witnessed the downfall of the Soviet Union.

“I was part of the last generation of the red-collared Soviet pioneers,” Dilshod said.

It was the Gorbachev era, and the grip of the Kremlin on Tashkent was loosening. Soon discussions about the independence of Uzbekistan started to be heard.

In 1991, the predominantly Muslim country became a sovereign state and President Islam Karimov came into power. Soon the country’s ties to Turkey, not so much with Russia, began to develop. Ankara started to invest heavily in the Uzbek education system. Dilshod was lucky enough to enter one of 14 Turkish-financed high schools. Before finishing school in 1999, he won second place in a national competition on “Native Language and Literature.” This won him the opportunity to enroll at Uzbekistan State World Language University.

In the same year, the Department of International Journalism was founded there at the initiative of Karimov. The United States supported this new department and sent personnel to teach Uzbek journalism students.

Tensions rising

By 2005, Dilshod had finished his master’s degree. The same year a massacre shocked the world: Uzbek authorities killed up to 1,500 protesters following unrests in the city of Andijan. As a consequence, the U.S. cut all ties to Uzbekistan. Most of Dilshods professors left the country, leaving many jobs vacant. Dilshod took the opportunity and started to teach journalism at his university.

But could he really speak freely about journalism in the authoritarian state? Under the rule of Karimov, all newspapers and TV stations had to follow the centralized news agency.

“It was just copy and paste,” Dilshod said angrily. “Even the photographs were the same.”

It was during this time the wish for a life in another country began to grow. Dilshod, now married and with a son, entered the yearly green card lottery held by the U.S. State Department. Each year 55,000 people from around the world hope to win a chance to start a new life in the United States. In 2015, after trying for seven years, Dilshod won the lottery.

“At first I didn’t even notice it. Only several weeks later I looked at the website and found out I’d won,” Dilshod said.

But winning the lottery doesn’t mean a free ticket to New York. You only win a chance to apply for one of the green card spots for you and your family. But first Dilshod had to pay a lot of money just to gather all the necessary health certificates. In November of 2015, he finally received the message he had been hoping for: He and his family were cleared to go to the United States.

New York, New Struggles

Upon arrival in New York Dilshod was welcomed by one of his cousins. During the freezing cold winter of 2016, he stayed in Brooklyn in a community of immigrants from former Soviet states. Here Dilshod got along easily just speaking Russian and Uzbek.

“My cousin hasn’t learned English to this day,” Dilshod said.

Dilshod disliked this kind of life. He wanted to interact more with U.S. citizens. With his focus on international journalism and politics in mind, he moved to Fairfax, Virginia, not far from Washington D.C. At first a friend gave him shelter so he could get his life together and wait until the snow-caused shutdown at the East Coast was over.

But Dilshod had to start from the bottom. At first, he began working at a pizza place.

“When I saved up a little money, I bought an old car so I could deliver the pizzas,” Dilshod said.

Later he bought a newer car and worked as an Uber driver on the side. In 2018 he finally learned that the online service “Voice of America” was looking for a social media expert to supervise its service in the Uzbek language.

Today, Dilshod provides articles about U.S. politics and his homeland to thousands of Uzbek-speaking people in their home country and in the diaspora. “Voice of America” has correspondents in Germany, Afghanistan and – as absurd as it may sound – in Uzbekistan. Many Uzbeks still don’t trust the newspapers and TV stations.

“Social Media is the news source most Uzbeks rely on,” Dilshod said.

Through the Internet, Dilshod can finally publish his texts, just as he always wanted: without fear of censorship.

To the article

Covid-19 and the lockdown in Uzbekistan and Germany

By Janek Kronsteiner